.jpg)

Emil FECHTNER

One of the Few

Jeden z hrstky

…………….* 16.09.1916, Prague.

…………….† 29.10.1940, Whittlesford, UK.

Pre WW2 :

Před 2. svět. válkou :

Emil Fechtner was born on 16 September 1916, in the Žižkov District of Prague, Czechoslovakia. The family later moved to Hradec Králové because of his father’s employment. There Emil attended grammar school, and successfully passed his school-leaving exam in June 1933, before finding work as a clerk.

Emil Fechtner se narodil 16. září 1916 v Praze, na Žižkově. Celá rodina se později přestěhovala do Hradce Králové, kde získal otec nové zaměstnání. Tam Emil navštěvoval gymnázium, kde složil v červnu 1933 úspěšně maturitní a poté začal pracovat jako úředník.

Emil Fechtner, 1937.

On 1 October 1935, for his compulsory military service, he was assigned to the 10th Regiment of the Czechoslovak Army, an artillery unit, from where he graduated, at the rank of podporučík (Lieutenant) which was the highest rank that could be achieved by a non-professional soldier. He was an ambitious young man and decided to become a professional soldier and in 1936 joined the Military Academy at Hranice in the Moravian region of Czechoslovakia. From there he graduated in 1937 and was posted to the 3rd Air Regiment ‘Gen. Milan Rastislav Štefánik’ which was deployed at Piešťany airbase in the Slovakia region of Czechoslovakia. There he joined the 38th Fighter Squadron which was equipped with Avia B-534 biplane fighter aircraft. In October 1937, he attended a pilot’s training course at the Military Aviation Academy at Prostějov, graduating in October 1938 as an operational pilot, and returned to the 38th Fighter Squadron in time for the general mobilisation in response to hostile demands from Nazi Germany.

1. října 1935 nastoupil povinnou vojenskou prezenční službu přidělen u dělostřelecké jednotky 10. pluku československé armády, kde také absolvoval v hodnosti podporučíka, což byla nejvyšší hodnost, jaké mohl dosáhnout neprofesionální voják. Byl mladý, ambiciózní a rozhodl se nastoupit dráhu profesionálního vojáka. V roce 1936 nastoupil do Vojenské akademie v Hranicích na Moravě. V roce 1937 zde absolvoval a byl vyslán ke 3. leteckému pluku Gen. Milana Rastislava Štefánika, který sídlil na letecké základně v Piešťanech na Slovensku. Tam byl přidělen ke 38. stíhací peruti, která byla nově vybavena stíhacími dvouplošníky Avia B-534. V říjnu 1937 absolvoval výcvikový kurz pilota na Vojenské letecké akademii v Prostějově, kde absolvoval v říjnu 1938 a jako operační pilot se vrátil zpět ke 38. stíhací peruti právě v době všeobecné mobilizace, v reakci na hrozící nebezpečí ze strany nacistického Německa.

Following the Munich Agreement of 30 September 1938, the Sudeten regions of Czechoslovakia were ceded to Germany, whilst other regions of Czechoslovakia were claimed by its neighbours; Poland occupied the Český Těšín region in the east, whilst Hungary occupied the southern regions of Slovakia and the Carpathian Ruthenia. During that tense period, the squadrons of the 3rd Air Regiment Air Force in Slovakia were mobilised in readiness to face the Hungarian Air Force if required.

Po mnichovské dohodě (30. září 1938) bylo území Sudet postoupeno Německu, zatímco některá další území Československa byla požadována jeho sousedy; Polsko si nárokovalo území Českého Těšína na východě, zatímco Maďarsko okupovalo jižní regiony Slovenska a Podkarpatskou Rus. Během tohoto vypjatého období byly perutě 3. leteckého pluku na Slovensku mobilizovány, aby byly v případě potřeby připraveny čelit maďarskému letectvu.

With the German occupation of Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939, Slovakia became ‘independent’ from Czechoslovakia, but in reality, just a puppet State for Nazi Germany. Emil and other Czech airmen serving in the Czechoslovak Air Force in Slovakia were returned to the German Protectorate. By this time he was already an experienced flyer and had achieved 229 flying hours to his credit.

Současně s německou okupací Československa dne 15. března 1939, získalo Slovensko „nezávislost“, ve skutečnosti se však jednalo o loutkový stát ve službách nacistického Německa. Emil a další čeští letci, sloužící v letectvu ČSA na Slovensku, byli odsunuti zpět do Protektorátu. V této době už byl zkušeným letcem a na svém kontě měl nalétáno 229 letových hodin.

Poland :

Do Polska :

With the German occupation of Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939, Slovakia became ‘independent’ from Czechoslovakia, but in reality, just a puppet State for Nazi Germany. Emil and other Czech airmen serving in the Czechoslovak Air Force in Slovakia were returned to the German Protectorate. By this time he was already an experienced flyer and had achieved 229 flying hours to his credit.The Czechoslovak Air Force was quickly disbanded by the Germans and all personnel dismissed; the same fate befell most of those serving in the Czechoslovak Army. Germanisation of Bohemia and Moravia began immediately. For the military personnel and many patriotic Czech citizens, this was a degrading period. Many sought to redress this shame and humiliation and wanted to fight for the liberation of their homeland. But by 19 March 1939, former senior officers of the now-disbanded Czechoslovak military had started to form an underground army, known as Obrana Národa [Defense of the Nation]. One of their objectives was to assist as many airmen and soldiers as possible to get to neighbouring Poland where Ludvík Svoboda, a former distinguished Czechoslovak Legionnaire from WW1, was planning the formation of Czechoslovak military units to fight for the liberation of their homeland. Within Czechoslovakia, former military personnel and civilian patriots covertly started to arrange for former Air Force and Army personnel to be smuggled over the border into Poland to join these newly formed Czechoslovak units.

Letecké síly ČSR byly okamžitě rozpuštěny a stejný osud postihl také ostatní složky armády ČSR. Pro příslušníky armády a vlastenecky cítící obyvatele to bylo ponižující období. Mnozí se snažili tuto hanbu a ponížení napravit. Germanizace Čech a Moravy začala okamžitě. Ale počínaje 19. březnem 1939 však bývalí vyšší důstojníci právě rozpuštěné československé armády založili vojenskou odbojovou organizaci, známou jako Obrana Národa. Jedním z jejích cílů bylo pomoci dostat co nejvíce letců a vojáků do sousedního Polska, kde Ludvík Svoboda, bývalý význačný československý legionář z 1. světové války, plánoval formování československých vojenských jednotek, které by bojovaly za osvobození své vlasti. V rámci Československa tak bývalí příslušníci armády a civilní dobrovolníci – vlastenci, začali tajně organizovat a zajišťovat přesun bývalých příslušníků letectva a armády přes hranice do sousedního Polska, aby se zde připojili k nově se utvářejícím československým jednotkám.

Obrana Národa also worked in co-operation with Svaz Letců, the Airman Association of the Czechoslovak Republic. These two organisations provided money, courier and other assistance to enable airmen to escape to Poland. Usually, this was by crossing the border from the Ostrava region into neighbouring Poland. News soon began to be covertly spread amongst the former Czechoslovak airmen and soldiers and many voluntarily made their personal decision to go to Poland. Emil was one of those who decided to escape and enlist in one of those units. He successfully managed to cross the border on 19 June 1939 and reported for duty at the Czechoslovak Consulate at Kraków.

Obrana Národa také spolupracovala se Svazem letců Československé republiky. Tyto dvě organizace poskytly peníze, převaděče a další pomoc, aby bylo letcům umožněno do Polska uprchnout. Obvykle se jednalo o překročení hranice do sousedního Polska někde na Ostravsku. Zprávy o této možnosti se brzy začaly tajně šířit mezi bývalými československými letci a ostatními vojáky a mnozí se dobrovolně rozhodli do Polska odejít. Emil byl jedním z těch, kteří se rozhodli do Polska uprchnout, aby tak rozšířili řady nově se formujících vojenských jednotek. Dne 19. června 1939 se mu podařilo překročit hranici s Polskem a v následujících dnech se už hlásil do služby na československém konzulátu v Krakově.

However Czechoslovak officials in Poland had been in negotiations with France, a country with which Czechoslovakia had an Alliance Treaty. Under French law, foreign military units could not be formed on its soil during peacetime. The Czechoslovak escapees, however, could be accepted into the French Foreign Legion with the agreement that should war be declared they would be transferred to French military units. The Czechoslovaks would, however, have to enlist with the French Foreign Legion for a five-year term. The alternative was to be returned to occupied Czechoslovakia and face German retribution for escaping – usually imprisonment or execution with further retribution to their families.

Avšak i v Polsku byli vojenští uprchlíci z Čech na horké půdě, neboť Polsko nesmělo na svém území organizovat vytváření zahraničních vojenských jednotek. Zástupci ambasády v Krakově však dokázali vyjednat na základě předválečné smlouvy o spolupráci s Francií přesun těchto jednotek do Francie. Podle francouzského práva však ani ve Francii v době míru nesměly být přítomny cizí vojenské jednotky. Jediné řešení pro československé vojenské uprchlíky byl vstup do cizinecké legie s tím, že v případě vstupu Francie do války budou tyto jednotky začleněny do francouzských vojenských jednotek. Čechoslováci se však museli upsat do Francouzské cizinecké legie na dobu 5 let. V případě odmítnutí by se museli vrátit zpět do okupovaného Protektorátu a čelit zde trestu za útěk – obvykle odnětí svobody nebo poprava, včetně perzekuce příslušníků jejich rodin.

Uprchlí dobrovolníci z Armády ČSR v Małých Bronowicích, léto 1939.

The Czechoslovak escapees were initially billeted at Bronowice Małe, a former Polish army camp outside Krakow, whilst arrangements were made for them to travel to France. After a short stay in Poland, Emil, along with 200 other escapees, mainly Czechoslovak airmen, travelled by train to the Polish Baltic port of Gdynia, where on 26 July they boarded the ‘SS Kastelholm’, a Swedish coastal steamer and set off for France. Part of the voyage down the Baltic Sea was very rough, even to airmen who were used to flying in turbulent conditions, and so the ‘SS Kastelholm’ stop at the Danish port of Frederikshaven to re-supply was a welcome relief for the Czechoslovaks onboard. After a five-day voyage, they arrived in Calais on 31 July.

Českoslovenští uprchlíci byli nejdříve ubytováni v Małých Bronowicích, bývalém polském vojenském táboře u Krakova, zatímco se sjednávaly podmínky jejich přepravy do Francie. Po kratším pobytu v Polsku pak Emil cestoval spolu s dalšími 200 uprchlíky, převážně československými letci, do polského přístavu Gdyně na Baltu, kde 26. července nastoupili do švédského pobřežního parníku SS Kastelholm a vydali se na cestu Francie. Část plavby po Baltském moři byla velmi bouřlivá, dokonce i pro letce, přivyklé létat v turbulencích, a tak zastavení „SS Kastelholm“ v dánském přístavu Frederikshaven, k doplnění zásob, přivítali všichni s úlevou. Po dalších pěti dnech plavby dorazili 31. července do Calais.

France:

Francii :

Initially, Emil and his fellow escapees were transferred to the Foreign Legion’s recruitment depot at Paris, to undergo medical checks, and the necessary documentation was made for their enlistment into the Legion pending their transfer to the Legion’s training base at Sidi bel Abbes, Algeria. During this time they attended French classes and any free time was usually spent in Paris exploring the sights and practising their newly learnt French with the girls they met.

Nejdříve byl Emil s ostatními převezeni do náborového střediska cizinecké legie u Paříže, aby zde podstoupili lékařské prohlídky, a do doby, než budou převedeni na výcvikovou základnu legií v Sidi bel Abbes v Alžírsku, mohla být zpracována jejich dokumentace pro jejich budoucí zařazení. Během této doby navštěvovali kurzy francouzštiny a volný čas obvykle trávili v Paříži prohlídkami jejích památek a procvičováním látky posledních lekcí francouzštiny s dívkami, které potkávali.

Emil Fechntner, Saint Cyr, France, 1940.

These arrangements were still not completed by 3 September 1939 when war was declared and so Emil was released from Legion service on 3 October to join l’Armee d’Air.Two days later he was posted, at the rank of Sgt to their training base at Centre d’Instruction de Chasse at Châtres airbase, near Paris, for re-training as a pilot on French MS 230 fighter aircraft. Amongst his colleagues, there were Vilém Göth, Vaclav Bergman, Emil Foit, František Burda, František Hradil, Vladimír Zaoral and Karel Vykoukal, all of whom were destined to become Battle of Britain pilots with him in England. During this period of their training, Emil and his fellow Czechoslovak airmen also attended École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, the French Officers Military Academy at Saint-Cyr, about 400 km west of Paris.

Tato opatření ještě nebyla ani dokončena, když Francie vyhlásila 3. září 1939 Německu válku. A tak byl Emil 3. října propuštěn ze služby legie, aby se připojil k l’Armee d’Air. O dva dny později byl vyslán v hodnosti Sgt na jejich výcvikovou základnu v de Chasse na letecké základně Châtres, nedaleko Paříže, aby se přeškolil jako pilot francouzských stíhacích letadel MS 230. Mezi jeho kolegy byli Vilém Göth, Václav Bergman, Emil Foit, František Burda, František Hradil, Vladimír Zaoral a Karel Vykoukal, všichni byli předurčeni stát se s ním v Anglii piloty bitvy o Británii. Během této doby jejich výcviku navštěvoval Emil a jeho českoslovenští spolubojovníci také kurz při École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, francouzské vojenské akademie důstojníků ve Saint-Cyr, asi 400 km západně od Paříže.

On 1 May 1940, he was promoted to rank of Lieutenant. On 23 May, having completed 13 hours of flying, was posted, with other Czechoslovak pilots at Chatres, to Cazaux, about 800 km away in south-west France but was not assigned to an operational unit. France capitulated before he could participate in the Battle of France. With the surrender of France on 22 June, Czechoslovak airmen were released from l’Armee d’Air service and those at Cazaux were instructed to get to Bordeaux,about 70 km away, for evacuation by ship to Britain before the advancing German army reached the port. At Bordeaux, the Czechoslovak airmen, under the command of Staff Capitan Josef Schejbal, as well as Poles and other nationalities boarded the ship ‘Karanan’, a small 395 tonne Dutch cargo ship, for the voyage to Britain. They sailed on 19 June and arrived two days later at Falmouth.

1. května 1940 byl Emil povýšen do hodnosti poručíka. Dne 23. května byl po absolvování 13 letových hodin vyslán spolu s dalšími československými piloty v Chatres do Cazaux, vzdáleného asi 800 km v jihozápadní Francii, ale nebyl už přidělen k operačnímu útvaru. Ještě než se mohl zúčastnit bojů, Francie kapitulovala. Když se 22. června Francie vzdala, byli českoslovenští letci ze služby v l’Armee d’Air propuštěni a ti v Cazauxu dostali pokyn, aby se přepravili do Bordeaux, vzdáleného asi 70 km, aby mohli být evakuováni lodí do Británie dříve, než tam dorazí postupující německá armáda. V Bordeaux nastoupili českoslovenští letci na cestu do Británie pod velením štábního kapitána Josefa Schejbala spolu s Poláky a dalšími příslušníky jiných národností na malou nizozemskou nákladní loď „Karanan“, o výtlaku 395 tun. Odpluli 19. června a o dva dny později dorazili do Falmouth.

RAF :

After arriving at Falmouth, the Czechoslovak airmen were transferred to RAF Innsworth, Innsworth, Gloucestershire for security vetting. Emil was accepted into the RAF Volunteer Reserve, at the rank of P/O and, at the beginning of July, transferred to the Czechoslovak airmen’s Depot at Cosford, near Wolverhampton. On 12 July, with other Czechoslovak pilots, he was posted to the newly formed 310 (Czechoslovak) Sqn which was based at Duxford, near Cambridge. They were equipped with Hurricane Mk I aircraft and commanded jointly by S/Ldr Alexander Hess, the first Czechoslovak to command an RAF squadron. and S/Ldr George D.M Blackwood.

Poté, co dorazili do Falmouthu, byli českoslovenští letci převedeni do RAF Innsworth, Gloucestershire aby zde podstoupili bezpečnostní prověrku. Emil byl přijat do dobrovolnické rezervy RAF v hodnosti poručíka a začátkem července byl převeden do československého leteckého skladu v Cosfordu poblíž Wolverhamptonu. 12. července byl spolu s dalšími československými piloty vyslán k nově vzniklé 310 peruti (československé), která sídlila v Duxfordu poblíž Cambridge. Ta byla vyzbrojena stroji Huricane Mk I a jejím velitelem byl major Alexander Hess, první československý velitel letky RAF., spolu s majorem George D.M Blackwood.

After rapid conversion to Hurricanes for the Czechoslovak pilots, and some basic English lessons, taught by Louis de Glehn, the squadron was declared operational on 17 August and made its first operational patrol at 14:10 that day. Emil had completed his Hurricane conversion and was passed for duties as an operational pilot. That afternoon, he and fellow Czechoslovak pilots P/O Rypl Sgt Hubáček, Sgt Řechka, led by F/Lt Jefferies made the squadron’s first operational patrol – a short 30-minute uneventful flight. It was the first operational flight in the Battle of Britain for these Czechoslovak pilots and Emil was flying Hurricane Mk NN-N, I P3148.

Po rychlém přechodu na stroje Hurricane a po několika vstupních lekcích angličtiny pro československé piloty, které vedl Louis de Glehn , byla letka vyhlášena za funkční a svůj první operační let provedla 17. srpna ve 14:10. Emil tak dokončil svůj přechod na stroje Hurricane a byl zařazen do služby jako operační pilot. To odpoledne provedl spolu s československými piloty P / O Ryplem Sgt Hubáčkem, Sgt Řechkou, vedeným F / Lt Jefferiesem, první operační hlídku letky – krátkým třicetiminutovým bezproblémovým letem. Byl to pro tyto československé piloty jejich první operační let v bitvě o Británii, Emil pilotoval stroj Mk NN-N, I P3148.

During the Battle of Britain, Emil made 51 operational flights and achieved combat success with 4 destroyed, 1 probable and 1 damaged Luftwaffe aircraft:

Během bitvy o Británii provedl Emil 51 operačních letů a jeho bojovými úspěchy byly 4 zničené, 1 pravděpodobný a 1 poškozený letoun Luftwaffe.

| Date | Time | Hurricane | Action Akce |

| 26/08/40 | 15:30 | P3143 | Me 109e, destroyed near Harwich. zničen poblíž Harwiche. |

| 31/08/40 | 13:30 | NN-S, P3889 | Do 17, destroyed North-East of London. zničen sv od Londýna. |

| 03/09/40 | 10:40 | NN-M, P3143 | Me 110, destroyed over Thames Estuary. zničen nad ústím Temže. |

| 07/09/40 | 10:40 | P3056 | Me 110 damaged South-East of North Weald airfield. poškozen jv od letiště North Weald. |

| 18/09/40 | 17:15 | NN-T, P8809 | Do 17, destroyed over Thames Estuary. zničen nad ústím Temže. |

| 27/09/40 | 12:40 | NN-S, L2713 | Do 17, probable over South-East London. pravděpodobně zničen nad jv Londýnem. |

For these achievements, he became the 2nd Czechoslovak airmen to be awarded the DFC, with the award ceremony being held on 27 October 1940.

Za tyto úspěchy se stal 2. československým letcem, který byl vyznamenán DFC, přičemž slavnostní předání cen proběhlo 27. října 1940.

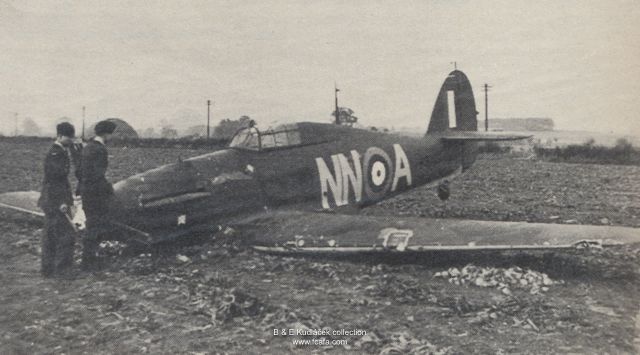

Two days after being awarded the DFC, he was killed in a flying accident. Shortly after taking-off from Duxford in Hurricane Mk I P3889, NN-S to patrol the Maidstone area, as Green section flight leader. About 1.5 km from the airfield his aircraft was in an aerial collision, at 13:55, at an altitude of 600 mtrs with the Hurricane Mk I P3707, NN-N of F/Lt Jaroslav Malý also of 310 Sqn and crashed at Whitlesford, near Duxford. His remains were found in the crashed aircraft and initially buried at the nearby cemetery at Royston. He was 24 years old and the eighth and last Czechoslovak pilot to be killed in the Battle of Britain.

Dva dny poté, co byl vyznamenán DFC, se zabil při letecké nehodě. Stalo se tak krátce po startu z letiště v Duxford v Hurricane Mk I P3889, NN-S, kdy byl vyslán s celou formací, aby hlídkovali nad oblastí Maidstone, jako vedoucí letky v zelené sekci. Asi 1,5 km od letiště, ve 13:55 hod. ve výšce 600 m se dostal jeho letoun do kolize se sousedním strojem Hurricane Mk I P3707, NN-N, pilotovaným F/Lt Jaroslavem Malým, rovněž z 310. perutě Sqn a zřítil se u Whitlesfordu, poblíž Duxfordu. Jeho pozůstatky, nalezené v havarovaném letadle, byly zpopelněny a pohřben byl na nedalekém hřbitově v Roystonu. Bylo mu 24 let a stal se osmým a také posledním československým pilotem, který položil život v bitvě o Británii.

Jaroslav Malý survived the collision but was slightly injured when he force-landed his aircraft at Fowlmere near Duxford.

Jaroslav Malý srážku přežil, byl lehce zraněn, když nouzově přistál se svým letounem u Fowlmere, poblíž Duxfordu.

Jaroslav Malý srážku přežil, byl lehce zraněn, když nouzově přistál se svým letounem u Fowlmere, poblíž Duxfordu.

P/O Emil Fechner was later re-interred in grave 28.E.1 in the Czechoslovak section of the Brookwood Military cemetery.

Tělesné ostatky P/O Emila Fechnera byly později přeneseny do hrobu číslo 28.E.1 v československé části vojenského hřbitova Brookwood.

_______________________________________________________________

Medals :

Medaile :

_______________________________________________________________

Distinguished Flying Cross (27. 10. 1940)

1939 – 45 Star with Battle of Britain clasp

_______________________________________________________________

Czechoslovakia / Československo :

Válečný kříž 1939 (28. 10. 1940)

Za chrabrost před nepřítelem

Za zásluhy I.stupně

Pamětní medaile se štítky F–VB

_______________________________________________________________

Remembered :

Pamětní místa :

_______________________________________________________________

Czech Republic :

Česká republika :

_______________________________________________________________

Prague 1 – Klárov :

Praha – Klárov :

In November 2017, his name, along with the names of 2507 other Czechoslovak men and women who had served in the RAF during WW2, was unveiled at the Winged Lion Monument at Klárov, Prague.

V listopadu 2017 bylo jeho jméno spolu se jmény dalších 2507 československých mužů a žen, kteří sloužili v RAF během 2. světové války, odhaleno na Pomníku okřídleného lva na pražském Klárově.

He is also remembered in the Remembrance book at St Vitus Cathedral, Prague 1.

Je rovněž připomínán v pamětní knize v katedrále Sv. Víta v Praze 1.

_______________________________________________________________

Prague 6 – Dejvice :

Praha 6 – Dejvice :

He is named on the Memorial for the fallen Czechoslovak airmen of 1939-1945, at Dejvice, Prague 6.

Jeho jméno je rovněž uvedeno na Památníku padlým československým letcům v letech 1939-1945 v Dejvice, Praha 6.

_______________________________________________________________

Great Britain :

Velká Británie :

_______________________________________________________________

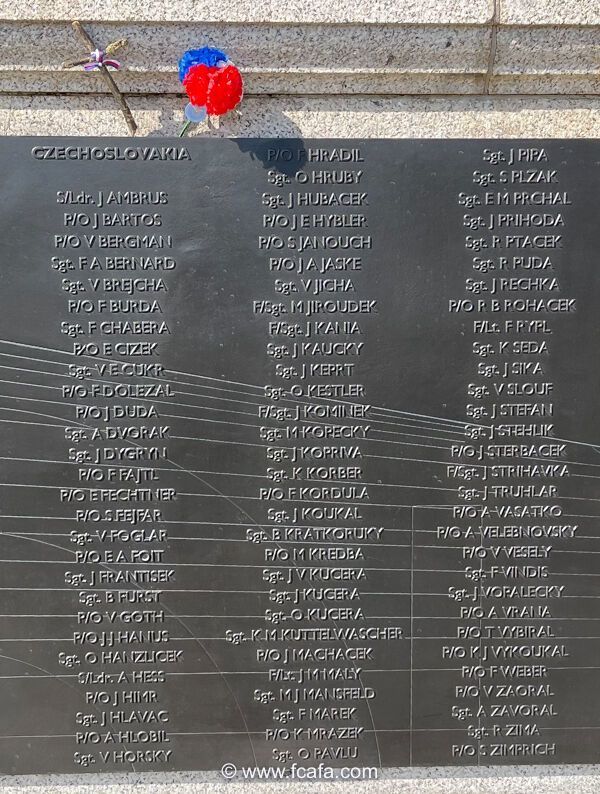

He is commemorated, along with the other 2938 Battle of Britain aircrew, on the Christopher Foxley-Norris Memorial Wall at the National Battle of Britain Memorial at Capel-le-Ferne, Kent:

Jeho jméno je připonuto, spolu s ostatními 2938 jmény z posádek bitvy o Británii, na pamětní zdi Christophera Foxleyho-Norrise v Národním památníku bitvy o Británii v Capel-le-Ferne, Kent:

_______________________________________________________________

He is commemorated on a memorial plaque by a tree planted near hangar 4 at Duxford to commemorate the Czechoslovak airmen who were killed in 1940/41 while stationed at the airfield.

Je připomínán také na pamětní desce umístěné na stromě u hangáru 4 který byl na letišti Duxford zasazen k připomenutí památky československých letců, kteří přišli v boji o život v letech 1940/41.

_______________________________________________________________

He is also commemorated on the London Battle of Britain Memorial:

Je připomenut také na Památníku bitvy o Británii v Londýně:

_______________________________________________________________

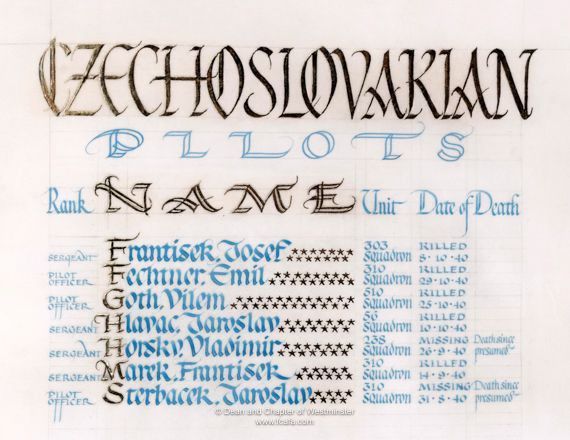

Battle of Britain Roll of Honour, RAF Museum, Hendon, London:

Deska cti bitvy o Británii, Muzeum RAF, Hendon, Londýn

_______________________________________________________________

target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”>Westminster Chapel, Westminster Abbey, London:Pamětní kniha ve Westminsterské kapli Westminsterského opatství, Londýn

_______________________________________________________________

London – St Clement Danes :

František Marek is remembered in the Remembrance book at St Clements Danes Church, London.

František Marek je zde vzpomenut v pamětní knize v kostele St Clements Danes v Londýně.

_______________________________________________________________

London – West Hampsted / Londýn – West Hampsted:

He is remembered on the Memorial Plaque at the Bohemia House, he former Czechoslovak National House, at West Hampsted, London.

Jeho jméno je připomenuto na pamětní desce na Bohemia House, bývalém Československém národním domě, ve West Hampstedu v Londýně:

_______________________________________________________________

He is commemorated, along with the other 2938 Battle of Britain aircrew, on the South West Battle of Britain Memorial at Weymouth, Dorset:

Je připomínán, spolu s ostatními 2938 posádkami bitvy o Británii, na jihozápadním památníku bitvy o Británii ve Weymouthu, Dorset:

_______________________________________________________________

Article last updated: 24.04.2024.

Hello, Emil Fechtner was my grandfathers uncle. This is more information than i had before, thank you for it.

Dobrý den, pane Musílku,

je dost nepravděpodobné, že by byl Emil Fechtner strýcem vašeho dědečka, naše rodina má velmi dobrý přehled o jednotlivých členech a je mi líto, ale nikam nám nepasujete.

Many of those who entered service who were Jewish, hid that fact behind a smoke screen. Jews were persecuted and the outcome of the war was not certain. I understand that those who did not wish to write down on paper that they were Jews gave themselves a less dangerous label. That didn’t mean they were truly Catholic or Lutheran or anything else. They wished to survive and fought bravely to do so. We should not forget that. This places the authorities in a difficult position because the men themselves put up a false denomination. The authorities are therefore obliged to follow what was written by the men themselves. It’s not a matter of anti-Semitism.

Dear Mrs. Paull,

I don´t know if you have read my clarification about Emil Fechtner´s religion. As his mother was surely Catholic, Emil Fechtner was also Catholic, he didn’t hide anything or make up a false identity about his religion.

Please, don’t search for signs of anti-Semitism in my answer, the other part of my family unfortunately was killed in concentration camps during the war.

Sincerely, Veronika Zakova

[Moderators Comment: Thank you Veronika. We can confirm that we have had sight of his birth registration document, which states that his religion was Roman Catholic. We trust, that this confirmation concludes this matter for all concerned.]

Martin Sugarman, it is unnecessary to aggressively apply your concerns to this article and website. These Czechoslovak airmen committed themselves and risked their lives against a fascist enemy on behalf of their country, not in order to make a religious statement.

hear hear!

Dear Mr. Sugarman, clearly there is a problem as to the religion of Emil Fechtner and Vilem Göth. I would like to draw your attention to the fact, that both Fechtner and Göth volunteered in the CZ Army abroad/RAF VR as ROMAN CATHOLICS. This is clearly written on their official military personal cards, which were written based on the information the the men provided when they volunteered as pilots. I have their military personal record cards, which I had taken in the Military History Archives in Prague, CZ. Since you are an archivist, perhaps you have the birth certificates of both men in your archive, or other official documents confirming that they were actually Jews. Could you please provide these? Then we can pose the question, whether they converted to Catholicism and if so, what was the reason. Thank you for providing is with documented information – very much appreciated! Letu zdar! Milena Kolarikova

Dear Mrs. Kolarikova, Dear Mr. Sugarman,

as Emil Fechtner was a cousin of my grandmother, I´m sure he was Roman Catholic. I know his mother Anezka Fechtnerova neé Liskova surely wasn´t Jew. I don´t know about his father Eduard Fechtner nothing closer, but as is commonly known, Jewishness is inherited by mother´s side.

Sincerely Veronika Zakova

Dear Veronika, thank you ever so much for confirming what FCAFA and myself believed to be true from day one. 🙂 Needless to say, Mr. Sugarman has yet to supply any relevant documents.

Dekuji Vam! Letu zdar, Milena

Thank you.

Dear Veronika, If your grandmother’s Christian name was Dana, I would very much like to come in contact with you, as she was, at the end of the war, a great friend of my mother, Colette Astié, from Chartres. I have personal documents about Emil and a photo of your grandmother. They were like sisters and worshiped the memory of Emil. I will also tell you more about Emil during his say in Chartres. It was a very sad and very moving story. Please feel free, if you get this message, to contact me directly.

Kind regards

Charles Astié-Griffith

ps : this site was given to me by Eva Mlásvoská, great grand daughter of A. Fechtnerová. It seems that, happily, not all the family was killed by the nazis.

pps : a letter from Anezka Fechtnerová to my mother in december 1962 indicates that the family used to go to the Czeck Brethen Church in Hrádec Kralové. So there is no doubt about who they were and what path of faith they followed. Le reste n’est qu’affirmation ridicule et sans fondement.

There is a Cross on the brown memorial and not a Star of David; WHY??? We remember them in our archives of the Jewish Military Museum in Camden (where I am Archvist) and in my article on ‘Jews in the Battle of Britain’ online or in my book, ‘Fighting Back’, as proud Czech Jews flying in the RAF against a common enemy – something you seem to forget and you fail DELIBERATELY to honour their ethnicity! What is that if not anti-Semitic racism???

[Moderators comment: As to why a Royal British Legion cross, and not a Star of David, was placed by this 310 (Czechoslovak) fallen airmen’s memorial plaque is a question you should be asking whoever placed it there – which, as previously mentioned was not ourselves.

Your usage of ‘Czech’ instead of Czechoslovak discriminates against the Slovak’s who were Czechoslovak nationals and also serving in the RAF and participants in the Battle of Britain. Those Czechoslovak remembered on that plaque were – irrespective of their denomination – were serving pre-WW2 in the Czechoslovak Air Force, in the service of their country, that role they continued when then joined the RAF.]

Fechtner and Goth both Jewish. Why hide it and lie about this with Crosses everywhere? The British Legion have Star of David pegs too.

This is racist

Martin Sugarman

[Moderator’s comment: Crosses ? there is only one photograph in this article that shows a Royal British Legion cross in respect of a memorial plaque for the 310 (Czechoslovak) Squadron airmen – of various denominations – who were killed while serving at RAF Duxford during WW2. This was not a Royal British Legion cross placed there by ourselves, but by someone who clearly wished to remember those fallen Czechoslovak airmen. A great pity that you see fit to use that person’s noble gesture as a platform to claim racism.]

May I ask you Martin, how or what you do to remember these Czechoslovak airmen, instead of blaming and complaining how they are remembered? Thanks for your answer.