The night of 24/25 March 1944 saw the most audacious Prisoner of War (PoW) escapes take place from Stalag Luft III (Stammlager Luft or Permanent Camps for Airmen) at Sagan, Germany (now Żagań, Upper Silesia, Poland), 100 miles south-east of Berlin. Seventy-six Allied PoW escaped from the camp that night in the best-conceived and largest organised Allied PoW escape of WW2, but one which was to have tragic consequences for the majority of those escapees.

V noci z 24. na 25. března 1944 se v Saganu v Německu (nyní Żagań, Horní Slezsko, Polsko) uskutečnil nejodvážnější útěk válečných zajatců z internačního tábora Stalag Luft III (Stammlager Luft nebo také tábory pro letce) jihovýchodně od Berlína. Sedmdesát šest aliančních válečných zajatců uniklo z tábora v noci v nejlépe koncipovaném a široce organizovaném útěku 2. světové války. Následky tohoto útěku však byly pro většinu jeho účastníků tragické.

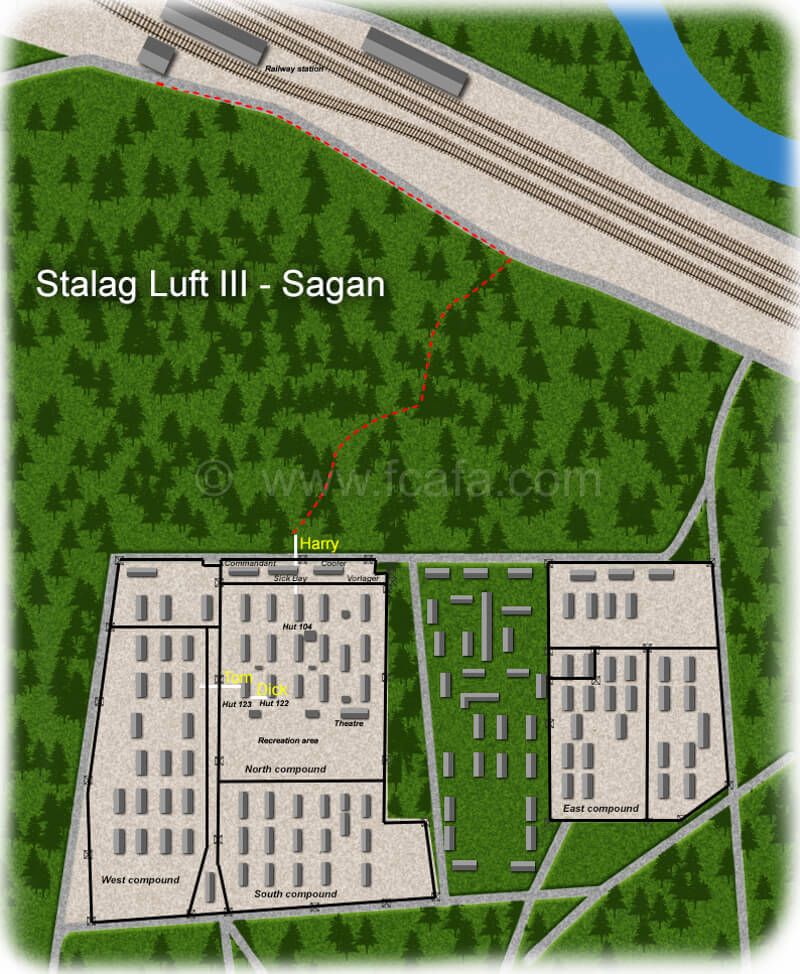

Stalag Luft III

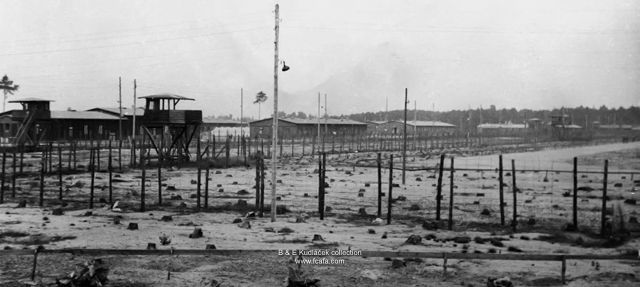

Stalag Luft III was a newly constructed prisoner of war camp, manned by some 800 German Luftwaffe personnel, for Allied Air Force personnel who had been shot down over German-occupied Europe. Its Commandant was Oberst (Colonel) Friedrich von Lindeiner-Wildau,, a career military officer who had served in the Prussian army in WW1 and the Luftwaffe since 1936.

Stalag Luft III byl nově postavený vojenský vězeňský tábor, jehož provoz zajišťovalo asi 800 zaměstnanců Luftwaffe a byl určen pro válečné zajatce z řad spojeneckých leteckých sil, kteří byli sestřeleni nad Německem obsazenou Evropou. Jeho velitelem byl plukovník Friedrich von Lindeiner-Wildau, kariérní armádní důstojník, který sloužil ještě v pruské armádě v 1. světové válce a v Luftwaffe pak od roku 1936.

The East compound was the first to be opened on 21 March 1942. The Centre compound was opened in April 1942, initially for RAF NCOs but by the end of that year, they were replaced by Americans. The North compound, from where the Great Escape took place, was opened in March 1943. The South compound was opened in September 1943 for the Americans with the West compound opened in July 1944 for American officers.

Východní sekce byla zprovozněna jako první 21. března 1942. Sekce centrální v dubnu 1942, a byla původně určena pro poddůstojníky RAF, ale na konci toho roku je vystřídali Američané. Severní sekce, kde se uskutečnil Velký útěk, byla zprovozněna v březnu 1943. Jižní část potom v září 1943, určená pro Američany, spolu se sekcí západní, kde byli američtí důstojníci.

Each compound consisted of 15 single-story raised wooden huts each containing sixteen 10 × 12 feet bunkrooms where 8 men slept in four double-deck bunk beds. Each hut also had three rooms for senior officers, a washroom, kitchen, and toilet. Eventually, the camp grew to around 60 acres in size and came to be home for about 2,500 Royal Air Force officers, about 7,500 U.S. Army Air Forces, and about 900 officers from other Allied air forces. The compounds also had a Vorlager area, which was a separate enclosure which had the compounds sick-bay and ‘cooler’ an isolation block for holding errant PoW’s in solitary confinement.

Každou sekci tvořilo 15 jednopodlažních dřevěných baráků, z nichž každá obsahovala šestnáct cimer o rozměrech 3 x 3,5 m, kde spalo 8 mužů ve čtyřech dvojlůžkových palandách. Každá barák měl také tři místnosti pro důstojníky, koupelnu, kuchyň a záchod. Po dokončení se tábor rozkládal na zhruba 60 akrech a stal se domovem pro asi 2500 důstojníků RAF a asi 7 500 amerických příslušníků armádních vzdušných sil a asi 900 důstojníků z jiných spojeneckých leteckých sil. Jednotlivé sekce měly také v uzavřeném prostoru svoje zdravotní zařízení s marodkou a isolací pro psychicky konfliktní pacienty.

It was the duty of all captured Allied officers during WW2 to try and escape from their PoW captivity. Thus some 600 prisoners in the North compound were involved in a plan to have 200 PoWs escape from the camp and attempt to make a ‘home run’ and return to England. The Senior Officer in this compound was Gp/Cpt Herbert Massey, whose bomber had been shot down over Holland in June 1942. The escape was masterminded by S/Ldr Roger Bushell, a South African pre-war barrister who had been captured when his Spitfire was shot down during the Dunkirk evacuation of May 1940. After several failed escape attempts he had been one of the first to arrive at Stalag Luft III’s East compound.

Spojenečtí důstojníci, kteří padli do zajetí během 2. svět. války, měli za povinnost pokusit se o útěk ze zajetí. Přibližně 600 vězňů v severní sekci se podílelo na realizaci plánu, jak připravit útěk pro zhruba 200 válečných zajatců, kteří by se pak pokusili dostat zpět do Anglie. Nejvyšším důstojníkem v této sekci byl Gp/Cpt Herbert Massey, jehož bombardér byl sestřelen nad Holandskem v červnu 1942. Útěk byl organizován S/Ldr Rogerem Bushellem, Jihoafričanem, před válkou obhájcem, který se dostal do zajetí poté, když byl jeho Spitfire sestřelen během evakuace u Dunquerke v květnu 1940. Po několika neúspěšných pokusech o útěk byl jedním z prvních, kdo dorazil do východní sekce Stalag Luft III.

That the camp was claimed by the Germans to be ‘escape proof’ – the site had been specifically selected because its sandy soil made it difficult to dig tunnels – only encouraged his fertile mind to begin examination of potential escape possibilities. Amongst his fellow PoWs were numerous experienced escapers who had previously made escapes from other PoW camps. These included some whose pre-war professions were conducive to escaping like mining engineers and surveyors for digging tunnels. Others had adapted peacetime interests into skills needed to escape; pre-war artists were now applying their skills to producing forged travel documents and maps, linguists were giving foreign language classes to would-be escapers. Some skills had been acquired in previous POW camps; tailors to dye and re-cut uniforms into civilian suits or workmen’s clothing; scroungers, to carry out the covert acquisition of materials, ranging from German travel documents and permits for the forgers to copy to tools and materials needed to construct tunnels and devious means of hiding soil excavated from the tunnels.

To, že samotní Němci klasifikovali tábor jako zabezpečený proti útěkům – místo bylo specielně zvoleno pro nesoudržnou písčitou půdu, ztěžující kopání tunelu – jen povzbudila jeho kreativní mysl a začal zkoumat všechny potenciální možnosti k útěku. Mezi jeho kolegy byla řada těch, kteří už měli zkušenost z útěku v jiném zajateckém táboře. Patřili mezi ně také ti, jejichž zkušenosti z předválečných profesí jako důlní inženýři nebo geodeti byly využity při kopání tunelů. Jiní zase přizpůsobili své dovednosti potřebám útěku; umělci využili svou preciznost k výrobě falešných dokladů a map; lingvisté vedli kurzy jazyka pro ty, kteří byli k útěku vybráni. Některé dovednosti získali vězni v předchozích zajateckých táborech. Krejčí přešívali a barvili vojenské uniformy na civilní nebo pracovní oblečení; chmatáci si šikovně “vypůjčovali” německé cestovní doklady a propustky pro padělatele, aby je mohli zkopírovat, kradli nástroje i materiál, potřebné ke stavbě tunelu, rafinovanými způsoby vynášeli a ukrývali vykopaný písek z tunelu.

Bushell and his Escape Committee ‘X’ devised their audacious escape plan; three tunnels would be constructed; one of which was bound to succeed, and 200 PoWs would exit through the tunnel and attempt to escape from German-occupied Europe; usually to a Baltic port and board a neutral ship to take them to Sweden, or to Switzerland, or across western Europe to Spain, or south to Yugoslavia and join up with Tito’s partisans.

Bushell a jeho Výbor pro útěk “X” vymysleli svůj odvážný plán útěku; bylo navrženo vykopat tři tunely; jeden z nich by měl uspět a 200 válečným zajatcům umožnit uniknout touto cestou z Evropy obsazené Německem. Snad do některého z přístavů v Baltském moři a nalodit se na neutrální loď, aby je dopravila do Švédska či Švýcarska nebo přes západní Evropu do Španělska nebo na jih do Jugoslávie a tam se připojit k Titovým partyzánům.

Some of the Allied officers were from Czechoslovakia, Poland, France, Belgium, Holland, Greece, Latvia and Norway. At that time the Czechoslovak RAF officers held in the north compound of the camp were; F/Lt Josef BRYKS, F/Lt František BURDA, P/O Emil BUŠINA, F/Lt Otakar ČERNÝ, F/Lt František CIGOŠ, P/O Bedřich DVOŘÁK, F/Lt Václav KILIÁN, F/Lt Karel KŘÍŽEK, S/Ldr Jiří MAŇÁK, F/Lt Josef ŠČERBA, F/Lt Ivo TONDER, F/Lt Karel TROJÁČEK, F/Lt Arnošt VALENTA and F/Lt Milan ZAPLETAL.

Někteří ze spojeneckých důstojníků byli z Československa, Polska, Francie, Belgie, Holandska, Řecka, Lotyšska a Norska. V té době byli příslušníci ČSR RAF drženi v severní části tábora; F/Lt František CIGOŠ, P/O Bedřich DVOŘÁK, F/Lt Václav KILIÁN, F/Lt Karel KŘÍŽEK, S/F František BURDA, F/Lt František BURDA, Ldr Jiří MAŇÁK, F/Lt Josef ŠČERBA, F/Lt Ivo TONDER, F/Lt Karel TROJÁČEK, F/Lt Arnošt VALENTA a F/Lt Milan ZAPLETAL.

Czechoslovak airmen who were PoW’s at Stalag Luft III.

Českoslovenští letci, kteří byli jako váleční zajatci ve Stalag Luft III.

Captured Czechoslovak RAF Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO) were also held in the NCOs compound at Stalag Luft III.

Zadržení českoslovenští poddůstojníci z řad RAF byli rovněž umístěni v poddůstojnickém oddělení ve Stalag Luft III.

The Tunnels

Tunely

For security reasons, the three tunnels, were named Tom, Dick, and Harry and all involved in the escape preparation were ordered to only refer to the tunnels by these names. Bushell threatened to court-martial anyone who even uttered the word ‘tunnel’.

Z důvodů utajení byly všechny tři tunely pojmenovány jako Tom, Dick a Harry a všichni účastnící, kteří byli do akce zasvěceni, měli nařízeno jinak tyto stavby nenazývat. Bushell dokonce vyhrožoval vojenským soudem komusi, kdo slovo “tunel” vyslovil.

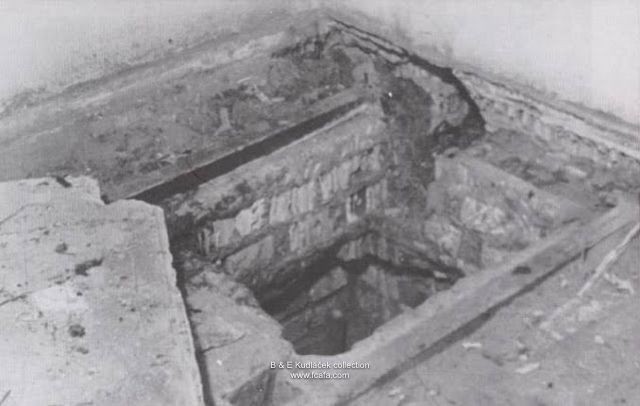

Looking up the top of the tunnel shaft.

Pohled vzhůru šachtou tunelu.

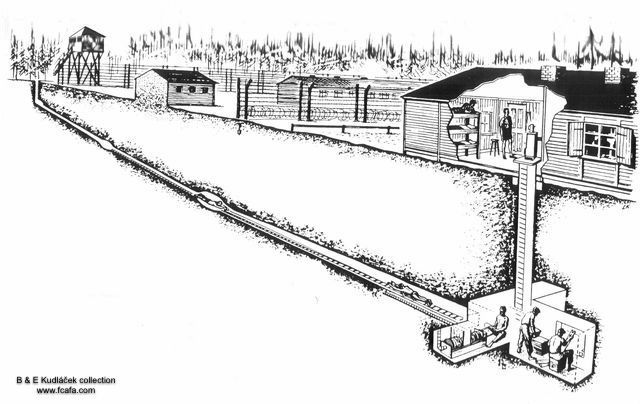

To avoid detection by the seismographs used to detect any tunnelling activity, the shafts for the three tunnels were dug very deep – about 30 ft (9 mtrs) below the surface. At the base of the shafts, chambers were constructed to provide a workshop and also where a crude air-pump was located to provide ventilation to the digging face of the tunnel. The tunnels themselves were very small just 2ft (0.6 mtr) square. The sandy walls and roof of the tunnels were shored up with wooden bed-boards taken from the PoW’s bunk-beds.

Aby se zamezilo prozrazení výkopů táborovými seizmografy, byly šachty všech tří tunelů posazeny velmi hluboko – přibližně 8 metrů pod povrchem. Toto ústí vstupní šachty sloužilo také jako úřadovna a dílna, v nichž byl umístěn ventilátor, který zajišťoval přívod vzduchu ke kopanému tunelu. Samotný tunel měl velmi úzký profil, pouze 60 cm v průměru. Stěny v písku a stropy tunelu byly zajišťovány výdřevou, získanou z boků a příčných prken pod matracemi postelí vězeňských paland.

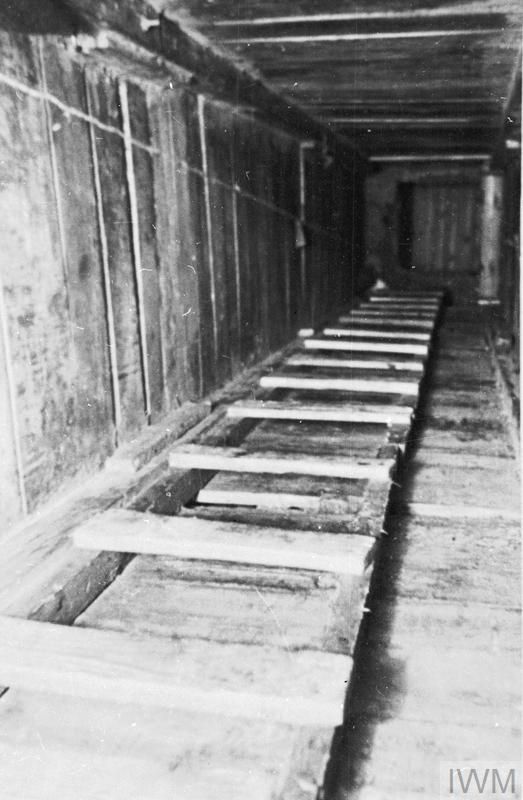

Tunnel ducting.

Potrubí ventilace tunelu.

Ducting for the ventilation was fabricated from dried milk tins (known as Klim tins) that came in Red Cross parcels. Initially, tunnel lighting was provided by home-made fat-lamps, which unfortunately gave off a foul vapour, causing the tunnellers to have headaches. Following a visit by some German electricians on a work detail into the camp, two large rolls of electrical wire was stolen from them, and connected into the camp’s electrical supply to power a number of light bulbs in each tunnel. To transport the tunnellers to and from the digging face and to remove the excavated sand, an underground trolley system was constructed, which was pulled by ropes. Digging tools were initially knives, forks and spoons until materials had been stolen or scrounged from the Germans, from which those in the workshops made small picks and shovels.

Větrací kanál byl zhotoven z plechovek od sušeného mléka (známých jako plechovky Klim), které se tam dostaly prostřednictvím Červeného kříže. Osvětlení výkopů tunelů bylo nejdříve zajišťováno podomácku vyrobenými tukovými svíčkami, které ovšem nechutně zapáchaly a způsobovaly kopáčům bolesti hlavy. Poté, kdy tábor navštívili němečtí elektrikáři a vězňům se podařilo odcizit dvě kluba el. vodičů, bylo osvětlení tunelů vyřešeno žárovkami, napojenými na el. rozvod táborových baráků. Pro přepravu kopáčů do a z výkopu tunelu a také pro přepravu vykopaného písku byl zkonstruován podzemní posuvný systém, ovládaný tažným lanem. Nástroje na těžbu zeminy byly zpočátku jen nože, vidličky a lžíce, dokud nebyly Němcům ukradeny předměty a materiál, ze kterého pak ti v dílně vyráběli sekáče a lopaty.

Tunnel trolley.

Posuvný systém.

Tom was started from a corner next to the stove in hut 123, it was dug westwards to emerge in the forest outside the camp’s perimeter wire. Some 70 tons of sand had been dug-out from the tunnel with around 1500 bed-boards used to shore the tunnel along its length. Unfortunately on 8 September 1943, when 260 ft (80 mtrs) long, it was discovered by chance when the Germans were making a search of the hut. They dynamited the tunnel to destroy it.

Tunel Tom začínal v rohu vedle kamen v baráku č. 123, vedl západním směrem a na povrch se dostal v lese za drátěným plotem tábora. Z tunelu bylo vytěženo asi 70 tun písku a použito asi 1500 prken z postelí pro bednění stěn po celé délce tunelu. Bohužel, 8. září 1943, když už byl dlouhý skoro 70 m, byl Němci při náhodné kontrole objeven. Tunel byl následně zničen pomocí výbušnin a zasypán.

Dick ran from hut 122 and went west, as this hut was further away from the camp fences and thus less likely to be a suitable location to start a tunnel. The tunnel entrance was hidden in a drain sump in the washroom of the hut and had the most secure trap door. Dick was abandoned for escape purposes in January 1944 because the area where it was planned to exit was now being cleared for the West compound; to dig beyond that expansion would have meant a length of some 500ft (150 mtrs). Dick had reached 60ft (18.2 mtrs) long requiring some 500 bed-boards to shore along its length and 30 tons of sand had been dug out. Dick was subsequently used to store sand dug out from Tom as well as to store escape materials and as a workshop.

Tunel Dick vedl z baráku 122 západním směrem, stál daleko od táborového oplocení, a jako začátek tunelu tak nebyl příliš vhodným místem. Vchod do tunelu byl ukryt v žumpě barákové umývárny a jeho vstup tvořil bezpečný poklop. V lednu 1944 se pro účely útěku přestalo s Dickem počítat, neboť vyšlo najevo, že oblast, kde měl být výstup z tunelu, je určena pro výstavbu západní sekce. Aby se tunel dostal na druhou stranu přes novou sekci, musel by mít alespoň 150 metrů. Dick měl v tu dobu asi 18 metrů bylo na něj potřeba 500 prken z pryčen na zpevnění stěn a vykopáno bylo kolem 30 tun písku. Dick byl potom využíván k ukládání písku, vynášeného z tunelu Tom a ke skladování předmětů potřebných k útěku a také jako dílna.

Underground plan of ‘Harry’.

Plán podzemí tunelu „Harry“.

Entrance to Harry, hut 104.

Vstup do „Harryho“, barák č. 104.

Harry, which began in hut 104, went under the Vorlager (which contained the German administration area, sick hut and the ‘cooler’ isolation cells) to emerge at the woods on the northern edge of the camp. The entrance was hidden under a stove. By the end of January ’44, Harry was 100ft long and the first switchover area – named ‘Piccadilly Circus’ was constructed. By mid-February, now 200ft long, a second switchover area – ‘Leicester Square’ – was constructed which made pulling the trollies through the tunnel much easier Digging was completed by mid-March 1944, and the tunnel was 364 ft (111.2 mtrs) long. Construction of Harry had required some 130 tons of sand to be dug out and some 2,000 bed-boards used for shoring.

Tunel Harry měl svůj vstup v baráku č. 104, vedl pod budovami Vorlageru (které tvořila Správa tábora, ošetřovna s marodkou a cely pro isolace vězňů), aby vystoupil na povrch v lese na severním okraji tábora. Vchod do tunelu byl skryt za kamny. Koncem ledna roku 1944 byl Harry 30 m dlouhý a byla zbudován první “přestupní” prostor – nazvaný „Piccadilly Circus“. Uprostřed února už to bylo 60 m a druhá “přestupní” stanice dostala jméno “Leicester Square”. Obě velmi usnadňovaly provoz tažného zařízení v ose tunelu. Výkop tunelu byl dokončen v polovině března 1944, a měřil celkem 111 metrů. Vykopání tunelu Harry představovalo vynosit asi 130 tun písku a stěny zpevnit asi 2000 prken z postelí.

One of the tunnel trolleys, now on display at the Sagan museum.

Jeden ze segmentů posuvného systému v muzeu v Saganu.

Other preparations

Ostatní přípravy

An escape on the large scale planned required a substantial infrastructure to help produce the necessary items to escape. The majority of the 600 officers who helped with this were well aware that it would be unlikely that they would be selected to be an escaper themselves, but there was always a possibility.

Útěk v takovém rozsahu vyžadoval důkladnou přípravu, která by pomohla zajistit nezbytnou výbavu všem, kteří budou k útěku vybráni. Většina z 600 důstojníků, kteří pomáhali s přípravou, si byla dobře vědoma malé pravděpodobnosti, že budou pro útěk vybráni právě oni; ale vždy tu existovala alespoň určitá naděje.

Whilst some were diggers in the tunnels, others helped in the workshop where they manufactured items needed for the tunnels. These items included crude air-pumps to provide ventilation at the digging face of the tunnel, which were made from wood and a kit-bag. Ducting pipes to carry that air through the tunnel were fabricated from dried milk (Klim) tins. The necessary shoring in the tunnel was made from bed-boards. Each bed originally used 20 boards to support the mattress; The PoWs reduced this to eight per bed, the remainder being requisitioned for tunnel shoring. The tunnel trolleys and the rails they ran on were similarly made from requisitioned timber like beading battens, tables, and bunk beds, from huts throughout the camp. Where materials and tools could not be scavenged in the camp, they were covertly stolen from visiting German maintenance men who came into the camp to undertake repairs. Two whole rolls of electrical wire were acquired this way – which was used to provide electric lighting in the tunnels.

Zatímco někteří pracovali jako kopáči, jiní pomáhali v dílně, kde se vyrábělo nářadí a nástroje potřebné pro hloubení tunelu. To zahrnovalo i primitivní vzduchové pumpy, kterými se vháněl čerstvý vzduch na čelo tunelu a které byly zhotoveny ze dřeva a vojenských toren. Trubky pro vedení čerstvého vzduchu tunelem, byly vyrobeny z plechovek od sušeného mléka. K výdřevě a opláštění stěn se používala prkna a desky z postelí. Každé lůžko mělo původně 20 prken jako podpěry pod matrace; vězni tento počet zredukovali na osm. Zbytek byl použit na tunelové ostění. Lanová tažná zařízení a kolejnice, po kterých se pohybovaly, byly podobně vyrobeny z upraveného dřeva, získaného z latí, stolů a paland z baráků po celém táboře. Tam, kde už nebylo odkud brát, byly některé materiály a nástroje tajně ukradeny německým údržbářům, kteří do tábora docházeli za účelem oprav a instalací. Tímto způsobem byly také získány dvě kluba drátu, který pak posloužil k zajištění elektrického osvětlení v tunelech.

The extent of the logistics needed to construct these tunnels can be ascertained from the materials ‘acquired’ for their construction: 4,000 bed boards had gone missing, as well as the complete disappearance of 90 double bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 192 bed covers, 161 pillow cases, 52 20-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 1,212 bed bolsters, 1,370 beading battens, 1219 knives, 478 spoons, 582 forks, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 1,000 feet of electric wire, 600 feet of rope, and 3,424 towels. Additionally, 1,700 blankets had been used, along with more than 1,400 dried milk (Klim) tins.

Rozsah logistického zázemí, nutného pro výstavbu těchto tunelů, si lze nejlépe představit z výčtu materiálů a počtu kusů, které bylo potřeba pro jejich výstavbu získat: zmizelo 4000 postelových prken, stejně jako se úplně ztratilo 90 patrových paland, 635 matrací, 192 pokrývek, 161 povlečení na polštáře, 52 stolů pro 20 osob, 10 jednoduchých stolů, 76 lavic, 1212 podhlavníků, 1 370 latí, 1219 nožů, 478 lžic, 582 vidliček, 69 svítilen, 246 kanystrů na vodu, 30 lopat, 300 m elektrického drátu, 180 metrů lana a 3424 ručníků. Navíc bylo použito 1700 dek a dále více než 1400 plechovek od sušeného mléka.

Above ground, a team of officers provided security; monitoring which Germans were in the camp and where they were at any one time. This ensured that other PoWs, working on escape preparations in the huts, would not be observed making escape material by an inquisitive German, or would be given adequate warning should they get too close.

Na povrchu hlídal ostražitý tým důstojníků. Prováděli sledování všech Němců, jejich přítomnost v táboře na tom kterém místě a ve kteroukoliv dobu. Tak bylo zajištěno, aby ostatní vězni, provádějící právě v barácích činnosti kolem příprav k útěku, nebyli přistiženi při této činnosti nějakým zvědavým německým dozorcem a mohli být včas varováni, pokud by se někdo takový nablízku objevil.

These Germans were also a source of documents which were of interest to the forgers to copy. Such documents, like ID cards and travel permits, would be covertly ‘borrowed’ from an unsuspected German for a short while the forgery team copied them. Another means of borrowing such documents or acquiring other escape materials; like a typewriter, paper, camera, photographic materials, railway timetables or maps was by bribery; the coffee, cigarettes, biscuits, soaps and other items that the PoWs received in their Red Cross parcels were highly desirable luxury items in war-torn Germany.

Od Němců pocházely také dokumenty, o které měli zájem padělatelé. Tyto dokumenty, jako průkazy totožnosti nebo cestovní propustky, byly na krátkou dobu tajně „vypůjčeny“ od nic netušícího Němce než je stačil tým padělatelů okopírovat. Dalším způsobem vypůjčení takových dokumentů nebo získání jiných potřebných předmětů jako psací stroj, papír, fotoaparát, fotografické potřeby, železniční jízdní řády nebo mapy, bylo úplatkářství; káva, cigarety, sušenky, mýdla a další předměty, které váleční zajatci dostávali v balíčcích od Červeného Kříže, byly velmi žádaným luxusním artiklem ve válkou zpustošeném Německu.

Bribery, or ‘covert acquisition’ was also used to obtain items of civilian clothing. The tailoring team converted many RAF uniforms, by cutting and dyeing, into civilian-style suits. Documents acquired were hand-copied by the forgery team to provide copies of ID cards, travel permits, employers letters and works instruction to help provide a believable background to their cover identity should the escapee be stopped by the authorities whilst on their escape. Portrait photos for the ID cards and travel permits were taken in an improvised photographic studio, which came complete with civilian suits, using the acquired camera and printed using materials obtained in the same way. Similarly, official rubber stamps were carved from boot heels.

Podplácení nebo „výměnný obchod“ bylo také používáno k získání civilního oblečení. Krejčovský tým upravil mnoho uniforem RAF jejich přešitím a přebarvením na civilní ošacení. Získané dokumenty byly ručně kopírovány týmem padělatelů, aby tak vyrobili kopie průkazů totožnosti, cestovních propustek, dopisů od zaměstnavatelů a pracovních povolení, které zajišťovaly věrohodné krytí pro případ, že by byl uprchlík při útěku kontrolován. Portrétní fotografie pro průkazy totožnosti a cestovní propustky byly pořízeny v improvizovaném fotoateliéru v civilním oblečení s použitím vykšeftovaného fotoaparátu a vyvolány pomoci materiálů, získaných stejným způsobem. Podobně tak byla úřední razítka vyřezána z gumových podrážek bot.

Maps covering the immediate area around the camp as well as many routes across occupied Europe to neutral countries, were duplicated with a camp-produced lithographic printer. Compasses were produced by melting down gramophone records, moulding into shape and adding a magnetised sliver of razor blade as a north pointer.

Mapy terénu bezprostředního okolí tábora, stejně jako řadu tras napříč obsazenou Evropou směrem k neutrálním zemím, byly kopírovány litografickým tiskem, vyrobeným v táboře. Kompasy byly vyráběny odléváním roztavených gramofonových desek do formy a připevněním zmagnetizovaného úzkého pásku ze žiletky, který ukazoval sever.

PoW’s exercing around the compound.

Váleční zajatci během vycházky v táboře.

The mammoth task of dispersing of the sand removed from the tunnels – a total of some 230 tons (21,000 kg) – was achieved by covertly dispersing it around the compound whilst on recreational walks, under, or in the roof-spaces of the huts, or adding to the numerous vegetable patches which the PoWs had started in the camp or hiding under the auditorium floor in the camp theatre, and eventually placed in Dick.

Mamutím úkolem bylo roznést a rozptýlit obrovské množství písku, vytěženého z tunelů – celkem asi 230 tun. Toho se v tajnosti podařilo dosáhnout jednak roznášením písku po celém prostoru tábora při procházkách vězňů, jeho ukládáním pod podlahy nebo do půdních prostor baráků a také na spoustu zeleninových záhonů, které vězňové za tím účelem v táboře založili. Písek se ukládal také pod podlahu hlediště táborového divadla a nakonec i do tunelu Dick.

The chosen few

Výběr účastníků

With Harry nearing completion came the difficult decision as to who were going to be the chosen 200 to escape. Altogether 510 names had been put forward into a draw for selection. The first 100 names were selected by the Escape Committee as those who had the best chance of making a successful escape or had made a marked contribution in the various preparations required to achieve the escape effort. From these selected 100 names, the first 30 were allocated because they were perceived, because of their language skills, excellent forged travel documents, and knowledge of Europe, to stand the best chance of making the elusive ‘Home run’.

Jak se blížilo dokončení tunelu Harry, nastalo těžké rozhodování o tom, kdo se stane jedním z těch 200, kteří dostanou šanci k útěku. Celkem se do širšího výběru přihlásilo 510 vězňů. První stovka jmen byla vybrána přímo Výborem pro útěk z těch, kteří měli nejlepší šanci při útěku uspět anebo se výrazně podíleli v různých činnostech, nezbytných pro přípravu útěku. Z těchto vybraných 100 jmen bylo prvních 30 předurčeno z důvodů jejich jazykových schopností, výtečné kvality jejich padělaných dokladů a znalostí evropského prostoru, což jim dávalo velkou šanci, aby byl jejich „Home run” úspěšný.

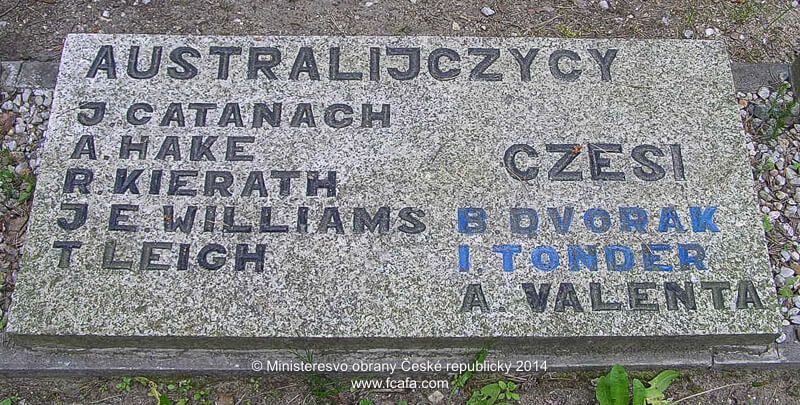

In this first group were DVOŘÁK, TONDER and VALENTA, because of their heavy involvement in the escape preparation – DVOŘÁK and TONDER as tailors and tunnel diggers, whilst VALENTA handled intelligence for the escape Committee by getting information from the Luftwaffe guards. S/Ldr Tom Kirby-Green was drawn as 24th to escape. In September 1939, he had been posted to 311 (Czechoslovak) Sqn until September ’41, to help train the Czechoslovak aircrews. Whilst there, he had made many friends in the squadron. He was then posted to 40 Sqn and his bomber was shot down on 17 October 1941 whilst on a raid on Duisburg, Germany.

V této první skupině byli také DVOŘÁK, TONDER i VALENTA, a to z důvodu jejich značných zásluh během přípravy útěku – Dvořák a Tonder jako krejčí a kopáč tunelu, zatímco Valenta přispěl svými zpravodajskými zkušenostmi získáváním informací od stráží Luftwaffe. S/Ldr Tom Kirby-Green byl vylosován jako 24. V září 1939 byl poslán k 311. peruti (československé) kde pomáhal až do září 41 zaškolovat československé posádky. Během té doby si u této perutě získal mnoho přátel. Poté odešel ke 40. peruti, kde byl jeho bombardér při náletu na německý Duisburg 17. října 1941 sestřelen.

The next selection was from 40 names, of which 20 were chosen; they would be the second group to exit Harry. The next draw was from 30 names of prominent workers in the escape, from which 20 were chosen. Those whose names had not been selected in the earlier draws were then drawn again and 30 names selected. F/Lt Josef BRYKS, a 242 Sqn Spitfire pilot who had been shot down on 17 June 1941 while on bomber escort duty on a raid on Lille, France, was 100th in that group.

Následný výběr byl proveden ze 40 jmen, z nichž bylo vybráno dalších dvacet; ti měli tvořit druhou skupinu, která Harryho opustí. Další výběr byl proveden ze 30 jmen, kteří se v přípravách útěku výrazně angažovali. Z nich bylo opět vybráno dalších 20. Ti, kteří ve všech předchozích výběrech neuspěli, se stali součástí dalšího seznamu a z nich pak bylo vybráno posledních 30 jmen do stovky. F/Lt Josef Bryks, pilot Spitfire z 242. perutě, který byl sestřelen 17. června 1941 při ochraně bombardovacího svazu během náletu na francouzskou Lille, byl právě jako stý.

The second 100 names were drawn at random from the remaining 410 names.

Další stovka účastníků útěku byla náhodně vylosována ze zbývajících 410 jmen.

The first 30 escapees would be provided with civilian suits, forged documents, train time-tables, maps and money to enable them to quickly get away from Sagan before the escape was discovered in the morning. For the remaining 170, the chances of making a successful escape were very slim as the majority would be on foot and the winter weather of deep snow and cold would be a severe obstacle. Their escape though would require the Germans to deploy tens of thousands of military, police and civilians to search for them and thus cause serious disruption.

Prvních 30 uprchlíků bylo vybaveno civilním oblečením, kvalitně padělanými doklady, jízdními řády, mapami i penězi, aby se dokázali dostat rychle z okolí Saganu, než bude ráno útěk prozrazen. Pro těch 170 zbývajících byly šance na úspěch minimální, neboť většina z nich se musela pohybovat pěšky v zimním počasí a hlubokém sněhu, což se jevilo jako vážná překážka. Jejich útěk navíc bude znamenat, že Němci rozmístí po okolí desítky tisíc vojáků, policistů i civilistů, kteří je budou hledat a jejich šanci uniknout tak velmi sníží.

Harry completed

Harry dokončen

The original plan was that the escape attempt would be made in summer, but in early 1944 the Gestapo had visited the camp and ordered an increased effort to detect escapes. Rather than waiting for the warmer summer weather and risk having their tunnel discovered, Bushell ordered the attempt be made as soon as it was ready. Harry was completed in mid-March 1944 – the first moonless night was the 24/25th – and so final preparations for the escaping 200 were made to escape on that night, about a year after construction of Harry had started.

Původní plán zněl, že pokus o útěk se uskuteční v létě, avšak počátkem roku 1944 navštívilo tábor gestapo a nařídilo zvýšenou ostrahu a úsilí k odhalení připravovaných útěků. A tak spíše než čekat na příznivější letní počasí a riskovat přitom, že jejich tunel bude objeven, Bushell rozhodl, že útěk se uskuteční jakmile bude tunel hotov. Harry byl dokončen v polovině března 1944 a první bezměsíčná noc byla z 24/25 a poslední přípravy na útěk 200 válečných zajatců se uskutečnily právě rok poté, kdy se s kopáním tunelu Harry započalo.

Break-out

Zdrháme

On the night of 24 March, as soon as it became dark, the 200 escapees from huts other than hut 104 covertly left their own huts to assemble in hut 104.

V noci z 24. března, jakmile se setmělo, 200 vyvolených se začalo z ostatních baráků postupně kradmo přesouvat do baráku číslo 104.

At around 20:40, the first of the escapees began to enter Harry. Meanwhile, chief diggers Johnny Bull and Johnny Marshall were already at the bottom of the exit shaft and Bull began to dig away the last few inches of soil from the top of the exit shaft. Unfortunately, the sand, wet from the snow, had caused the wooden hatch cover to swell, making it difficult to open. Finally, after a lot of struggling, they succeeded in removing the cover and dug out the final few inches of soil to open up the tunnel exit. It was now 22:15, more than an hour later than the scheduled time.

Kolem 20:40 vstoupil do Harryho první z uprchlíků. Mezitím, šéf kopáčů Johnny Bull s Johnny Marshallem už byli na dně výlezové šachty a Bull začal kopat těch posledních pár centimetrů půdy v horní části šachty. Bohužel, písek zvlhký od sněhu způsobil, že dřevěné víko poklopu nabobtnalo a nešlo vyrazit. Konečně, po velkém zápase, se podařilo kryt uvolnit a vykopat zbývající decimetry půdy, aby se dostali z tunelu ven. To však už bylo 22:15, více než o hodinu později, než bylo plánováno.

Disaster

Katastrofa

But when Bull, raised his head out of the tunnel, he was shocked to find that the tunnel was some 25 feet from short of its intended exit point amongst the safety of the forest. Instead, the exit was in exposed ground and only about 45 feet from one of the guard towers. With guards patrolling around the outside of the camp, the chances of escapers being seen exiting the tunnel were very high, particularly against the snow.

Když však Bull vystrčil hlavu na povrch, byl šokován, neboť zjistil, že tunel je alespoň o 7 metrů kratší než bylo zamýšleno, aby byl výstup ukryt mezi stromy lesa. Namísto toho se nacházel na otevřeném místě, necelých 15 metrů od jedné ze strážních věží. Pravděpodobnost, že uprchlíci budou při výlezu z tunelu spatřeni některým ze strážců byla vysoká, zejména při sněhové pokrývce.

With this unexpected error with their survey calculations, a hasty meeting was taken by Bushell and his team in the tunnel – do they abort the escape tonight, seal up the tunnel entrance, dig the extra distance and then wait a month for the next moonlight night and go then, or do they improvise an exit procedure and stay with the existing plan to escape that night? The realisation that all their forged travel documents were dated for that day and that to redo completely new documents for 200 escapees would take several months, made the decision for them: they would have to go that night. They quickly improvised an escape signaling system: one of the escapees would exit the tunnel with a rope, and take cover in the nearby trees. The other end of the rope was secured in the tunnel; two tugs on the rope would mean it was safe to exit the tunnel and cross open ground into cover in the depth of the woods.

Tato neočekávaná komplikace přiměla Bushella a jeho tým ke spěšné schůzce, aby rychle rozhodli co dál – odložit dnešní útěk, uzavřít výstup z tunelu, dokopat potřebnou vzdálenost a pak čekat na další bezměsíčnou noc nebo improvizovat při výstupu z tunelu a zůstat u původního plánu utéci dnes? Při vědomí, že všechny jejich padělané cestovní doklady a propustky nesly aktuální datum a padělat nové pro 200 lidí by trvalo několik měsíců, rozhodnutí znělo: útěk musí proběhnout tu noc. Rychle vymysleli improvizovaný signalizační systém pro výstup z tunelu: jeden z uprchlíků vylezl z tunelu s lanem a ukryl se za nejbližší stromy. Druhý konec lana byl upevněn ve výlezu. Dvojí škubnutí lana znamenalo, že je bezpečné opustit tunel, překonat otevřený terén a pokračovat ve skrytu lesa.

The Escape

Útěk

The escapers route from ‘Harry’ to Sagan railway station.

Trasa útěku z výstupu tunelu k nádraží v Saganu (Žagani).

It was now 22:30, 90 minutes behind schedule, when the first of the escapers began to exit Harry. The initial group of escapees had planned to walk through the woods in pairs to Sagan railway station from where they would catch various trains to their onward destinations. However the 90-minute delay caused many to miss their trains and resulted in various groups of escapees congregating at the station, whilst they waited for alternative trains.

Bylo už 22:30, 90 minut zpoždění oproti plánu, když tunel opustil první uprchlík. První skupina měla po dvojicích projít lesem k nádraží v Saganu, odkud měli pokračovat různými vlaky do svých směrů. Nicméně, 90 minut zpoždění způsobilo, že svoje původní spoje zmeškali a na nádraží se začaly tvořit skupinky těch, kteří čekali na příští spoje.

Ticket hall at Sagan railway station.

Hala s pokladnami železniční stanice v Saganu.

The escape was almost rumbled at the station by Hannelore Zöller, one of the German mail censors, who with a friend had been into town to see a film and was making her way back to the camp via the subway at the railway station. On passing through the booking hall they noticed “two or three little groups of strange-looking men” waiting for a train. They are “extraordinarily dressed” and look “somewhat nervous”. She raised her concerns with a railway official who fortunately was not interested and dismissed them

Útěk byl na stanici téměř prozrazen Hannelore Zöller, jednou z německých cenzorek táborové pošty, která byla s kamarádem ve městě v kině, a vraceli se nádražním podchodem zpět do tábora. Při průchodu kolem pokladen si všimli „dvou nebo tří malých skupin podivně vypadajících mužů“, kteří čekali na vlak. Byli „divně postrojení” a zdáli se „poněkud nervózní“. Se svým podezřením se svěřila železničnímu úředníkovi, kterého to naštěstí nezajímalo a jejich obavy odmítl.

Back at the tunnel, things were not going as planned; instead of the estimated 2 to 3 minutes for each escaper to travel through the tunnel, it was actually taking 5 to 6 minutes and in some cases longer. By 23:30 only six of the 17 escapees in the first group had exited the tunnel.

Mezitím se v tunelu nic nedařilo podle plánu; namísto odhadovaného intervalu 2 až 3 minut, kdy se měl každý dostat skrz tunel, to trvalo 5 až 6 minut a v některých případech i déle. Z první skupiny opustilo do 23:30 hod. tunel pouze šest ze 17 uprchlíků.

Around this time, air-raid sirens sounded as Allied bombers approached on their way to bomb Berlin. All the floodlights surrounding the camp were switched off, which meant that the tunnel light also went out. Fat lamps in the tunnel were quickly lit, As with the floodlights extinguished, it gave an excellent opportunity for more to exit the tunnel under cover of darkness.

V tu dobu se okolím rozlehl zvuk sirén, který ohlašoval blížící se letecký nálet na Berlín. Veškeré osvětlení tábora i okolí bylo vypnuto, což znamenalo, že také tunel se ocitl ve tmě. Tak byly rychle rozžaty lojové svíčky, protože zhasnuté světlomety a úplná tma byly skvělou příležitostí jak urychlit úprk z tunelu.

Whilst the air-raid helped to get a few more out, it was becoming obvious to the tunnel controllers in hut 104 that with all the delays, that realistically there was little chance of all the planned 200 escapers being able to get out.

Zatímco nálet pomohl řadě dalších dostat se ven, bylo organizátorům útěku v baráku 104 zřejmé, že pro všechna ta zpoždění je jen malá naděje, aby se všech plánovaných 200 vězňů dostalo ven.

At around 02:00, with the passing of the Allied bombers, the air-raid sirens ceased and camp floodlights came back on. In Harry, the electric lights also worked again but they were still slow to get people through the tunnel. Around 05:00, with dawn about to break, the controllers in hut 104, decided that no. 87 would be the last man to go through the tunnel. However, at the tunnel exit escaping was about to be aborted. S/Ldr Len Trent, the 79th man had just exited the tunnel when a patrolling guard began to approach the tunnel exit and became suspicious about the slush and footprints, sounded the alarm and fired his rifle as he stumbled across Trent who immediately surrendered. (Trent was a 28-year-old New Zealand bomber pilot who had been awarded the Victoria Cross for outstanding leadership on his final flight when he was shot down over Holland on 3 May 1943).

Kolem 02:00 hod., poté, co spojenecká letadla proletěla a sirény ukončily poplach, byly světlomety v táboře opět rozsvíceny. Uvnitř Harryho tak bylo opět dostatek světla, ale průchod uprchlíků tunelem začal opět váznout. Kolem 05:00 hod., s počínajícím rozbřeskem, se organizátoři útěku v baráku 104 rozhodli, že posledním šťastlivcem bude číslo 87. Avšak na výstupu z tunelu došlo k zádrhelu. Právě když S/Ld. Len Trent, muž s číslem 79, opouštěl tunel, přiblížil se k výstupu z tunelu strážný, který pojal podezření, když si ve sněhové břečce povšiml řady stop, vyhlásil poplach a vystřelil, když málem zakopl o skrývajícího se Trenta. Ten se okamžitě vzdal. (Trent, 28 letý novozélandský pilot bombardéru, nositel vyznamenání Viktoriina kříže za vynikající počínání během svého posledního letu, než byl sestřelen nad Holandskem dne 3. května 1943).

In hut 104, on hearing the shots, they realised that the tunnel had been discovered. The would-be escapers frantically began eating their escape rations before they were confiscated and destroying their forged documents by burning them in the stove.

Když se ozvaly výstřely, bylo všem baráku 104 jasné, že tunel byl objeven. Všichni, kteří už nestihli stát se uprchlíky, začali horečně pojídat obsah svých balíčků na cestu než jim budou sebrány a zničeny a pálili svoje padělané falešné osobní doklady v kamnech.

The Germans carried out an immediate roll-call so they could identify who had escaped: Seventy-six airmen had escaped, and a nationwide alert was called by the Germans to hunt them down. Three of the 76 escapers were Czechoslovak, P/O Bedřich DVOŘÁK, F/Lt Ivo TONDER and F/Lt Arnošt VALENTA. Their stories:

Němci okamžitě vyhlásili nástup, aby zjistili kdo všechno z tábora unikl: chybělo 76 letců a Němci vyhlásili celostátní pohotovost, aby mohli být zadrženi. Tři ze 76 uprchlíků byli Čechoslováci – P/O Bedřich DVOŘÁK, F/Lt Ivo TONDER a F/Lt Arnošt VALENTA. Zde jsou jejich příběhy:

_______________________________________________________________

The Czech escapers

P/O Bedřich Dvořák

P/O Bedřich Dvořák

P/O Bedřich Dvořák was a 30 year old 312 Sqn pilot whose Spitfire had been shot down into the English Channel whilst on Circus 6, escort duties to Allied Boston bombers on a raid on Cherbourg harbour, on 3 June 1942. He bailed out of his aircraft, but broke his arm on landing in the Channel. After about an hour he was rescued by a French fisherman, who was afraid of the consequences of helping Allied airmen. So, on reaching France, he handed Dvořák to the Germans. His Prisoner of War number was 39648. Initially, he was sent to Dulag Luft, at Frankfurt, Germany, then to hospital for treatment for his injuries on 16 June, then to Oflag IX-A/Z on 6 July, then on to Oflag IX-A/H, Spangenberg, Germany on 116 July. He was transferred to Stalag Luft III, at Sagan on 8 March 1943. Here he joined the escape organisation and worked alongside 34 others, including Ivo Tonder, in the ‘tailoring department’ where they adapted service uniforms into civilian suits for escapers, a role that earned him priority among escapers for the Great Escape.

P/O Bedřich Dvořák byl tehdy 30ti letý pilot 312. perutě, jehož Spitfire byl 3. června 1942 sestřelen nad Lamanšským průlivem, když zajišťoval doprovod aliančních bombardérů Boston při náletu na přístav Cherbourg. Z letadla se mu podařilo vyskočit padákem do moře, zranil si ruku a asi po hodině byl vyloven francouzskými rybáři. Ti se ovšem obávali následků za pomoc aliančnímu letci a s omluvami jej na pevnině předali Němcům. Jako válečný zajatec dostal číslo 39648. Nejprve byl poslán do Dulag Luft, ve Frankfurtu, v Německu, poté 16.6.1942 do nemocnice na doléčení zranění a dále 6.11.42 do Oflag IX-A , Spangenberg. Nakonec byl přemístěn do Stalag Luft III v Saganu (dnes Žagaň, Polsko) dne 8. března 1943. Zde se přidal do skupiny, která připravovala útěk a spolu s dalšími 34 zajatci, včetně Ivo Tondera, pracovali v “krejčovském oddělení”. Zde přešívali služební uniformy na civilní oblečení pro útěk, což mu umožnilo, aby byl zařazen jako jeden z účastníků tohoto “Velkého útěku”.

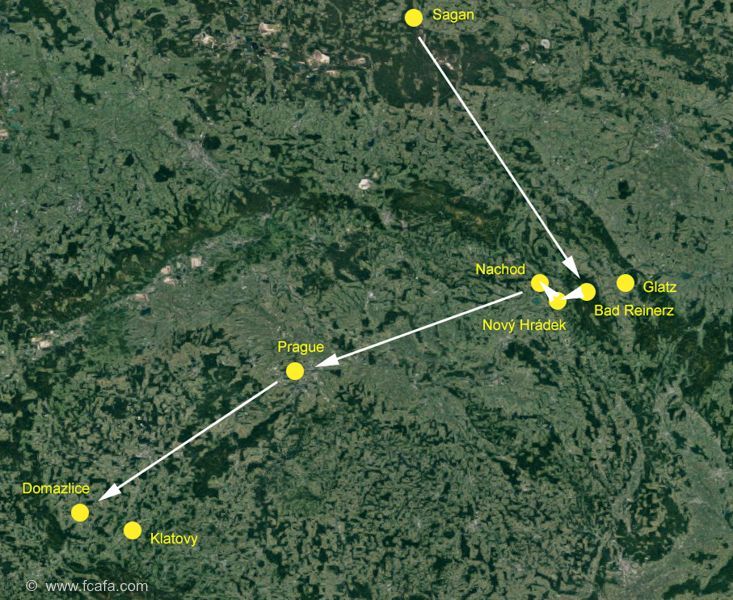

For the escape, he partnered with Des Plunkett, a 29 year old bomber co-pilot from 218 Sqn. Dvořák was fluent in German, French and English as well as his native Czech, Plunkett was a native English speaker with some knowledge of Czech. Their papers said they were Siemens technicians from Breslau, who were going on holiday to Czechoslovakia. They planned to go by train from Sagan to Breslau and then on to Glatz, which was about 30 miles from the Czechoslovak border, to which they intended to walk. Once in Czechoslovakia, they planned to travel to Kbely, Prague, where they had arranged to meet at a friendly hotel with fellow escapers Valenta, Tonder and their respective escape partners. From here Dvořák and Plunkett planned to go by train to near the Swiss border, just two days away, and cross into Switzerland on foot.

Pro útěk vytvořil dvojici s Des Plunkettem, 29ti letým spolubojovníkem z 218. perutě. Dvořák hovořil plynule německy, francouzsky a anglicky, stejně jako svojí rodnou češtinou. Plunkett byl rodilý Angličan s částečnou znalostí češtiny. Byli vybaveni doklady jako technici firmy Siemens z Breslau (dnes Wroclav, Polsko), kteří cestují na dovolenou do Československa. Plánovali jet vlakem ze Saganu do Breslau a pak vlakem do Glatzu (dnes Kladsko, Polsko), které bylo už jen 30 kilometrů od hranic s Československem, které hodlali překročit. Jakmile se ocitnou v Československu, plánovali cestovat do Kbel u Prahy, kde se měli setkat v bezpečném hotelu se svými kolegy z útěku – Valentou a Tonderem. Odtud se Dvořák s Plunkettem chystali jet vlakem k švýcarským hranicím, kam by dorazili po dvou dnech a pěšky pak přešli na švýcarskou stranu.

His Escape:

Jeho útěk:

P/O Bedřich Dvořák’s escape route.

Trasa útěku Bedřicha Dvořáka.

The delay in being able to exit the tunnel meant that several of the ‘train escapees’ had missed their earlier trains and so instead of just a few escapees arriving at Sagan railway station in time to catch their trains, a backlog had built had up to catch the later trains. Further confusion was caused at the station, as after the Sagan Escape Committee had surveyed the station, a shed had been built by the subway entrance into the station, resulting now in various groups of escapers having difficulty in finding that entrance.

Zdržení při průchodu tunelem způsobilo, že řada uprchlíků zmeškala své dřívější vlaky, a tak jen pár z nich svoje vlaky stihli, zatímco zbytek musel použít spojů pozdějších. K dalším zmatkům došlo na stanici samotné, neboť od doby, kdy Výbor pro útěk prozkoumal prostory stanice, došlo k výstavbě nového podchodu a některé skupinky prchajících měly problém vstup do nádraží vůbec nalézt.

The entrance to Sagan railway station that the RAF escapers had to go through.

Vstup do železniční stanice Sagan, kudy museli váleční zajatci RAF při útěku projít.

As Dvořák and Plunkett approached the station they heard the sound of approaching Allied bomber aircraft on their way to bomb Berlin. With air-raid sirens now sounding, Dvořák pulled Plunkett into the subway entrance and they went to the ticket office. However there the lady in the office refused to sell them tickets and instructed a German soldier to take them to the air-raid shelter. Just then the 01:00, Berlin-Breslau express train began pulling into the station, distracting the soldier. They exploited that distraction and slipped away through the ticket barrier and boarded the last carriage of that train– on hearing the air-raid sirens, the train-driver had promptly started to leave the station.

Když se Dvořák s Plunkettem blížili k nádraží, uslyšeli zvuk sirén protileteckého poplachu spojeneckých bombardovacích letadel při jejich náletu na Berlín. Za zvuků sirén protileteckého poplachu vtáhl Dvořák Plunketta do průchodu nádraží a namířili si to k pokladně. Nicméně dáma v pokladně jim za této situace odmítla vystavit jízdenky a německý voják je posílal do protileteckého krytu. V tu chvíli, v 1.00 hod., vjížděl právě do nádraží rychlík Berlín-Breslau, který odvedl vojákovu pozornost. Využili toho a vyklouzli z prostoru pokladny na peron a nastoupili do posledního vagonu. Strojvedoucí pod dojmem sirén oznamujících nálet, okamžitě vyjel s vlakem ze stanice.

At about 02:30 the train pulled into Breslau and they quickly joined the crowd of people, leaving the train and making their way past the railway police and through the ticket barriers, and exited the station without attracting any attention. They had now missed their train connection to Glatz, (now Kłodzko, Poland, since 1945) and checking the timetables found the next train was at 06:00. They noticed several other Sagan escapers were also there in the same predicament of having missed their train connections. There was little option but to settle down inconspicuously in the booking hall, ignoring their fellow escapees, and tensely waiting for their 06:00 train. On its arrival, they boarded the crowded local train that would be stopping at each station on the journey to Glatz. It was an unnerving journey as a German lad in Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) uniform, tried to engage them in conversation, so they feigned exhaustion and eventually the lad gave up and went off.

Kolem 2:30 hod. dorazil vlak do Breslau a zde se rychle vmísili do davu cestujících, kteří z vlaku vystupovali, prošli kolem železniční policie, přes turnikety a vyšli z nádraží, aniž by vzbudili pozornost. Teď museli čekat na vlakové spojení do Glatz ( Kłodzko, Polsko) a ověřili si, že nejbližší vlak jede až v 06:00. Všimli si že je tu s nimi také několik dalších uprchlíků se stejnou nesnází chybějícího vlakového spojení. S malou nadějí, že nevzbudí pozornost, se usadili v čekárně a ignorujíce své souputníky, čekali na svůj vlak v 06:00. Místní lokálka přijela přecpaná a zastavovala cestou do Glatz na každé zastávce. Byla to nervy drásající cesta, neboť jakýsi německý mladík v uniformě Hitlerjugend se snažil s nimi navázat rozhovor, takže museli předstírat únavu dokud to mládenec nevzdal a nevzdálil se.

After four hours, the train reached Glatz. Whilst the snow had now stopped, it was still bitterly cold and, with their exhaustion, the two did not look forward to the 30-mile cross-country hike to the Czechoslovak border. They revised their plan and instead bought train tickets to Bad Reinerz (now Duszniki-Zdrój, Poland) which was just 15 miles from the Czechoslovak border. They arrived at Bad Reinerz in a heavy snowstorm and set off cross-country, in hip-deep snow and across difficult terrain, to Nový Hrádek, which was just inside the Czechoslovak border, arriving there at 20:00 on 25 March; they were now about 100 miles from Sagan. At Nový Hrádek, they went to a small inn, asked to see the manager, identified themselves as escaped RAF officers, and asked for help. The inn was family-run and within a few minutes, they were taken through to the inn’s lounge, sat down by a hot stove and hot food was brought to them. By the following morning, however, the inn-keeper was having second thoughts as to the consequence to him and his family if the Germans were to find out that he had been assisting PoW escapers and arranged for them to stay at a farmers barn about 7 miles, a three hour walk away.

Po čtyřech hodinách jízdy vlak dorazil do Glatz (Kladska), přestalo sice sněžit, ale oběma byla hrozná zima a tak se při své únavě na 45 km tůru k československým hranicím nevydali. Přehodnotili svůj původní záměr a raději si koupili lístky na vlak do stanice Bad Reinerz (dnes Duszniki-Zdrój, Polsko), odkud to bylo ke hranici už jen něco přes 20 km. Do Bad Reinerz dorazili za silné sněhové vánice ve 20.00 hod. 25. března a hned vyrazili hlubokým sněhem a členitým terénem na Nový Hrádek, který byl už na československé straně hranice. V tu dobu byli nějakých 160 km od Saganu (dnes Žagaň, Polsko). V Novém Hrádku se rozhodli navštívit místní hostinec, vyžádali si vedoucího a představili se mu jako důstojníci RAF na útěku a požádali ho o pomoc. Hostinec byl provozován jako rodinný a během několika minut byli převedeni do hostinského salonku, posadili se k vyhřátým kamnům a dostali teplé jídlo. Avšak druhý den ráno si hostinský začal uvědomovat možné následky pro sebe a svoji rodinu, kdyby Němci zjistili, že pomáhá válečným zajatcům a navrhnul jim ukrýt se ve stodole, vzdálené asi 12 km, necelé 3 hodiny pěšky.

They left the barn on 31 March and made their way north to the railway station at Náchod. There, a policeman asked to see their papers and was sceptical about their cover story of being Siemens technicians from Breslau, but let them proceed to the ticket office and purchase tickets to Pardubice for the following morning. Their train left at 08:00 and on arrival there they caught a connecting train which took them to Prague.

Stodolu opustili 31. března a vydali se na sever, směrem k nádraží v Náchodě. Tam byli požádáni českým strážníkem o doklady a jakkoliv se mu moc nezdála jejich pohádka o technicích Siemensu z Breslau, nechal je jít k pokladně, kde si koupili jízdenky do Pardubic. Jejich vlak odjížděl v 08:00 hod. a tam stihli přípoj, kterým se dostali až do Prahy.

On arrival there, they walked to Kbely, on the outskirts of Prague, where there was a small hotel whose proprietor who had previously helped an RAF escaper and who they hoped would be able to assist them. However, with the nearby military airfield now used by the Luftwaffe, the inn was now used as a billet for some of the Luftwaffe personnel and so too dangerous to stay there. Instead, the proprietor arranged for them to visit a barber in the Libeň district of Prague who was able to help them with travel documents and clothes.

Po příjezdu do Prahy se vydali do Kbel, na okraji Prahy, kde Dvořák věděl o malém hotýlku, jehož majitel už v minulosti letci RAF při útěku pomohl a doufali, že bude schopen pomoci i jim. Avšak poté, kdy byl personál blízkého vojenského letiště, nyní využívaného Luftwaffe, ubytován právě v tomto hotelu, bylo nanejvýš nebezpečné hledat azyl právě tady. Místo toho majitel zařídil, aby navštívili holičku v pražské Libni, která jim pomohla obstarat cestovní doklady a oblečení.

On 7 April, they continued their journey westwards from Prague towards Switzerland, boarding a train for Domazlice, near the German border. The train stopping at Tábor, where there was a short delay, then onto Písek, where again there was a delay, finally arriving at Domazlice at 6pm. They were now about 180 miles from Sagan.

Dne 7. dubna pokračovali v cestě do Švýcarska vlakem směr Domažlice, poblíž německých hranic. Vlak stavěl v Táboře, kde bylo krátké zdržení a pak ještě v Písku, kde opět nabrali zpoždění, až nakonec dorazili do Domažlic v 18 hodin. V tuto chvíli byli asi 300 km od Saganu.

They stayed at an inn but became concerned at the scrutiny the inn-keeper gave their ID cards. They decided that on their departure the next day they would back-track on their journey and instead go east to Klatovty, about 17 miles away, in case they had been reported to the police.

Zastavili se v hospůdce, kde však byli podrobeni prohlídce svých osobních dokladů. Na základě toho se rozhodli, že druhý den nebudou pokračovat k hranicím a namísto toho se vydají východním směrem na Klatovy, vzdálených nějakých 25 km. To vše z obavy, že o jejich přítomnosti je už informována policie.

The following morning, at Domazlice railway station, Dvořák went through at the police checkpoint first, with no problems, but Plunkett was stopped and questioned by a Czech protectorate policeman. Dvořák went back to help and argued with the policeman, who demanded that they accompany him to the local police station so that their ID cards could be checked out. After an hour in the cells there, the policeman advised them that their ID cards were false and that they were to accompany him to the Gestapo office. When it became apparent that the Gestapo were convinced that the two were paratroopers who had been parachuted in from England, Dvořák and Plunkett had little option but to admit that they were escaped RAF officers. They were then returned to their cells to await their fate, little comforted by a Czech policeman who told them that they would be shot.

Následující ráno na železniční stanici v Domažlicích prošel Dvořák policejní kontrolou bez problémů, avšak Plunkett takové štěstí neměl a byl zadržen českým protektorátním policistou. Dvořák se vrátil, aby mu pomohl, hádal se s policistou, který však vyžadoval, aby jej oba doprovodili na místní policejní stanici, kde budou ověřeny jejich osobní doklady. Asi po hodině je policejní strážník vyrozuměl, že jejich doklady jsou falešné a že budou předvedeni na Gestapo. Když bylo zřejmé, že gestapo je přesvědčeno o tom, že se jedná o výsadkáře z Anglie, Dvořák s Plunkettem neměli jinou možnost, než přiznat, že jsou důstojníci RAF na útěku. Byli vráceni zpět do vazby, kde očekávali svůj osud s malou nadějí, když i český policista jim předpověděl smrt zastřelením.

On 4 May, they were collected by Gestapo car and taken Petschko Palace, the Gestapo headquarters in Prague for further interrogation, where he was to be re-united with Ivo Tonder. On 21 November they were both transferred from Pankrác prison to Prague’s Hradčanský Domeček military prison, on 30th of that month they were transferred to Stalag Luft I, at Barth. Two weeks later they were taken to Leipzig for a show-trial, were they were tried for treason, as by serving in the RAF, they were traitors to the Reich Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren, the new German name for occupied Czechoslovakia, and sentenced to death. And on 8 January 1945, they were sent to Oflag IVc – Colditz – to await the said execution. *** They were held there until 16 April when the castle was liberated by the Americans.

Dne 4. května byli odvezeni vozem Gestapa do Petschkova paláce, velitelství gestapa v Praze, k dalšímu výslechu, kde se znovu shledal s Ivo Tonderem. Dne 21. listopadu byli oba převezeni z věznice Pankrác do pražského vojenského vězení Hradčanského domečku. Dne 30. listopadu byli převeleni do Stalag Luft I v Barthu. O dva týdny později byli odvezeni do Lipska k soudnímu přelíčení, obžalováni ze zrady protektorátu Böhmen und Mähren, protože sloužili v RAF, odsouzeni k smrti a 8. ledna 1945 byli posláni do Oflag IVc – Colditz, aby zde čekali na vykonání rozsudku. *** Byli tam drženi až do 16. dubna, kdy byl objekt osvobozen Američany.

Des Plunkett was also to survive. On 25 January 1945, he was transferred to Stalag Luft I, Barth. It was here that he was to learn of the Gestapo execution of the 50 Stalag Luft III escapers. On 1 May 1945, the camp was liberated by the advancing Russians and he and the other British PoWs were repatriated back to the UK.

Des Plunkett také přežil. 25. ledna 1945 byl přemístěn do Stalag Luft I, Barth, kde se dozvěděl o popravě 50 vězňů ze Stalag Luft III. Dne 1. května 1945 byl jeho tábor osvobozen postupujícími Rusy a on a ostatní britští váleční zajatci byli dopraveni zpět do Velké Británie.

_______________________________________________________________

F/Lt Ivo Tonder

F/Lt Ivo Tonder

F/Lt Ivo Tonder was a 29 year old 312 Sqn pilot whose Spitfire had been damaged in aerial combat with Fw 190s over France whilst on Circus 6, escort duties to Allied Boston bombers on a raid on Cherbourg harbour, on 3 June 1942. On the return flight to England, a fire broke out behind the cockpit, forcing him to bail-out, at about 16:00, into the English Channel, off Cherbourg. He managed to inflate his dinghy and after some five hours a Luftwaffe Heinkel 59 seaplane spotted him and landed to capture him at 08:00. His Prisoner of War no. was 561.

F/Lt Ivo Tonderovi bylo 29let, byl pilotem u 312. perutě, když byl jeho Spitfire poškozen ve vzdušném souboji s Fw 190 nad Francií, kde se účastnil ochranného doprovodu pro alianční bombardéry Boston při jejich útoku na přístav Cherbourg, dne 3. června 1942 (akce Cirkus 6). Při zpátečním letu k anglickým břehům vypukl za jeho kokpitem požár, který ho donutil kolem 16.00 hod. opustit nad Kanálem, poblíž Cherbourg, svůj letoun. Podařilo se mu nafouknout člun a po pěti hodinách ho zpozoroval hydroplán Luftwaffe, Heinkel 59, přistál na hladině, aby ho zajal a vzal na palubu kolem 8:00. Jako válečný zajatec dostal číslo 561.

Initially taken to Dulag Luft, Oberursel, for interrogation by the Germans Tonder was then transferred to Stalag Luft III, Sagan, on 16 June 1942. Here he made two aborted escape attempts prior to being one of the 76 escapees of the Great Escape of 25 March 1944. During his time at Stalag Luft III, he was active in the ‘tailoring department’, alongside Bedřich Dvořák, as well as being a prolific tunneller, despite his claustrophobia. He was involved in digging the 8 mtr shafts down to the start of the tunnel; on one occasion, when the tunnel was a good 40 meters long, it collapsed and buried him. First of all, his fellow tunnellers managed to make a small hole through to him so that he could breathe. He then had to lie completely still for about 45 mins whilst they dug him out. He felt the smallest movement would cause more sand to fall, which would mean he’d suffocate; that 45 mins felt like an eternity. He was extracted from the tunnel collapse and given a week off from digging, which he later said he really needed.

Nejdříve byl poslán do Dulag Luft, Oberursel, kde absolvoval výslech a poté převelen 16. června 1942 do Stalag Luft III, Sagan. Zde se účastnil dvou nezdařených pokusů o útěk ještě předtím, než byl jedním ze 76 účastníků Velkého útěku z 25. března 1944. Během svého pobytu ve Stalagu Luft III působil spolu s Bedřichem Dvořákem v krejčovském “oddělení”, stejně jako byl výkonným tunelářem. Účastnil se prací na kopání 8mi metrové šachty, odkud měl tunel začínat. V době, kdy byl tunel vykopán již v délce 40 m, došlo k sesuvu písku, který jej zavalil. Jeho kamarádi museli nejdříve vytvořit malý otvor, kterým by mohl dýchat. Potom musel 3/4 hodiny ležet bez hnutí, zatímco ho ostatní vykopávali. Cítil, že nejmenší pohyb může způsobit další sesuv písku, což by znamenalo, že se udusí; oněch 45 minut mu připadalo jako věčnost. Když se jej podařilo ze závalu vytáhnout, byl na týden od kopání osvobozen. Později přiznal, že takovou úlevu velmi potřeboval.

His Escape:

Jeho útěk:

F/Lt Ivo Tonder’s escape route.

Trasa útěku Ivo Tondera.

For the escape, Tonder partnered with F/O Johnny Stower, a 28-year-old Wellington bomber pilot from 142 Sqn. They were 21st and 22nd respectively out of the tunnel and planned to get to Switzerland via Czechoslovakia. Their papers showed that Tonder was Czech and Stower was Spanish, (he was born in Argentina and was fluent in Spanish) that they were engineers at the Focke-Wulf factory and were going to Mladá Boleslav on holiday. They had arranged to meet with Bedřich Dvořák, Des Plunkett, Arnošt Valenta and Johnny Marshall in Prague.

Při útěku vytvořil dvojici s F/O Johnnym Stowerem, osmadvacetiletým pilotem bombardéru od 142. perutě. Tunel opustili jako 21. a 22. člen útěku. Jejich plánem bylo dostat se do Švýcarska přes Československo. Jejich doklady byly připraveny tak, že Tonder byl český a Stower španělský inženýr (narodil se v Argentině a mluvil plynně španělsky), z továrny Focke – Wulf a jedou právě do Mladé Boleslavi na dovolenou. Bylo plánováno, že se setkají s Bedřichem Dvořákem, Des Plunkettem, Arnoštem Valentou a Johnny Marshallem v Praze.

They exited the tunnel around midnight and made their way to Sagan railway station and had originally planned to catch the 01:00 train to Laubau, near the Austrian border. The delays in the tunnel meant that they were late getting to the station. They missed their train and noticed the backlog of fellow escapers, who had also missed their train connections. Instead of waiting for another train, they decided to make their way on foot through the snow. Walking South and keeping to the woods for cover, they managed to reach Halbau (now Iłowa, Poland), about 12 miles away and slept in the woods during the day (25th).

Okolo půlnoci opustili tunel a vydali se na železniční stanici v Saganu, kde chtěli původně stihnout vlak v 01:00 do Laubau, poblíž rakouských hranic. Zdržení v tunelu ale způsobilo, že přišli na stanici pozdě, vlak zmeškali a také zaregistrovali přítomnost ostatních kamarádů na útěku, kteří také čekali na příští vlak. Oni se však rozhodli jít pěšky sněhem. Vydali se na jih, drželi se poblíž lesa, aby se mohli skrýt a dostali se tak až do Halbau (dnes Ilowa, Polsko), vzdáleného asi 20 km. Během dne (25.) spali v lese.

That night they continued South through the woods and reached Kouhlfurt (now Węgliniec, Poland). However, on the morning of 27 March, their luck nearly ran out; at about 07:00, as they were approaching Stolzenberg (now Sławoborze, Poland), they were spotted by a young girl who informed the local authorities. Luckily, Tonder and Stower managed to avoid the three civilians and dog who came searching for them. They waited near Rothwasser (now Czerwona Woda, Poland) for the search to finish and then made their way make back to Kouhlfurt. There they bought food and 3rd class train tickets to Görlitz.

Další noc pokračovali dále na jih v lese a dostali se do Kohlfurtu (nyní Węgliniec, Polsko). Avšak ráno, 27. března se jejich štěstí unavilo; asi v 07:00, když se blížili k Stolzenbergu (nyní Sławoborze, Polsko), byli spatřeni mladou dívkou, která informovala místní úřady. Naštěstí se Tonder se Stowerem dokázali vyhnout třem civilistům se psem, kteří po nich pátrali. Čekali poblíž Rothwasser (nyní Czerwona Woda, Polsko), dokud pátrání neskončilo a pak vyrazili na cestu zpět do Kohlfurtu. Zde si koupili jídlo a jízdenky 3. třídou na vlak do Görlitz.

Arriving at Görlitz, they went to the ticket office where Tonder bought tickets for Reichenberg, Germany. Behind him in the ticket queue was a young SS officer who was becoming suspicious about them. To Tonder’s dismay, as he left the ticket-office window, he noticed the tickets were for another destination. Brazenly, taking the initiative, Tonder, in deliberately bad German, asked the SS officer for assistance, saying that the ticket office must have misunderstood him, and could the officer help. The brazen approach worked and the SS officer forced his way to the front of the queue and exchanged the tickets for the correct ones. Hardly believing their luck, Tonder thanked the officer, and quickly left the ticket office with Stower and boarded their train.

Tam šli ke staniční pokladně, kde Tonder koupil jízdenky do německého Reichenbergu (dnes Liberec, ČR). Za ním ve frontě stál mladý SS důstojník, kterému se zdáli být podezřelí. Když Tonder opouštěl okénko pokladny, všiml si ke svému zděšení, že jízdenky jsou vystaveny do jiného místa. Tonder drze převzal iniciativu a záměrně špatnou němčinou požádal důstojníka SS, zda by mu nepomohl s výměnou lístků u pokladní. Drzost slavila úspěch a důstojník SS se protlačil k okénku a jízdenky jim u pokladní vyměnil za správné. Tonder nemohl uvěřit jaké měl štěstí, důstojníkovi poděkoval a rychle se Stowerem od pokladny vypadli a nastoupili do vlaku.

However, their luck was short-lived. Just 25 miles later, after Zittau, en-route to Reichenberg (Liberec, Czechoslovakia), two plain-clothed German officials, and several military police entered their compartment for a routine paper check. The documents were returned with little interest after just a cursory glance but, on leaving the compartment, one of the policemen looked back and took a close look at Stower’s trousers. They were Royal Australian Air Force blue, and the policeman had seen that same colour just the previous day on another Great Escaper, who was now held at the police station at Liberec. The policemen became suspicious and began a thorough search of them; they found English chocolate, cigarettes and their PoW ID tags in their case. They arrested them and took them to the civilian prison at Reichenberg, some 55 miles from Sagan.

Avšak jejich štěstí nemělo mít dlouhého trvání. Měli za sebou asi 40 km jízdy, když za Zittau, na cestě do Reichenbergu , vstoupili do jejich oddílu dva němečtí úředníci a několik vojenských policistů za účelem rutinní kontroly osobních dokladů. Po zběžné kontrole a bez většího zájmu jim byly dokumenty vráceny, ale při odchodu se jeden z policistů ohlédl a svůj pohled zaměřil na Stowerovy kalhoty. Ty byly ušity z modré látky královského australského letectva a policista si uvědomil, že stejné viděl předchozí den na jednom ze zadržených účastníků útěku, který byl ve vazbě na policejní stanici v Liberci. Policisté pojali podezření a důkladně oba prohledali. Našli anglickou čokoládu, cigarety i jejich identifikační štítky válečných zajatců, zatkli je a odvezli do civilního vězení v Reichenbergu. V době zatčení byli asi 80 km od Saganu.

There, Tonder and Stower were to meet four of their fellow escapers – S/Ldr Johnny Bull, F/O Jerzy Mondschein, S/Ldr John ‘Willy’ Williams and F/Lt Reginald ‘Rusty’ Kierath – who had been captured the day before. The two groups were kept in separate cells, but they managed to have a brief chat, in which Tonder and Stower learned that the four fellow escapees had suffered rough interrogations, in which Willy Williams was told that he would be shot. Before any further conversations could take place the four were collected by the Gestapo, at 04:00, on 29 March for return to Sagan; they were executed on that journey and their bodies cremated at Brüx later that morning. The four urns were returned to Stalag Luft III.

Tam se Tonder se Stowerem setkali se čtyřmi kolegy z útěku. Byli to – S/Ldr Johnny Bull, F/O Jerzy Mondschein, S/Ldr John ‘Willy’ Williams a F/Lt Reginald ‘Rusty’ Kierath, kteří byli zatčeni den předtím. Obě skupiny byly drženy odděleně, ale podařil se jim krátký rozhovor, v němž se Tonder se Stowerem dozvěděli, že jejich čtyři kolegové byli tvrdě vyslýcháni a Willy Williamsovi bylo řečeno, že bude zastřelen. Dříve než mohli v komunikaci pokračovat, byla čtveřice gestapem deportována ve 04:00, 29. března zpět do Saganu; během této cesty však byli popraveni a jejich těla spálena v Brüx později toho dopoledne. Do Stalag Luft III se tak vrátily jen jejich čtyři urny.

At 08:00, 31 March, the Gestapo came to collect Stower for return to Sagan; he was executed later that morning during the journey and his body cremated at Liegnitz. His urn was returned to Stalag Luft III.

Dne 31. března, v 8.00 hod ráno si přišlo gestapo pro Stowera, že bude převezen do Saganu; namísto toho byl během cesty popraven a jeho tělo spáleno v Liegnitz. Do Stalag Luft III byla vrácena jeho urna.

Tonder believed that he had been left at Reichenberg because he was Czech and thus was going to received ‘special attention’ from the Gestapo. He remained there until 17 April when a guard came to his cell and told him that he was being collected and returned to Sagan. He was instead taken to Prague, and ironically had to direct his captors to Pankrác prison as they had not been to Prague before.

Tonder věřil, že byl ponechán v Reichenbergu, protože byl Čech a „těší“ se u gestapa zvláštní pozornosti. Zůstal tam až do 17. dubna, kdy do jeho cely přišel strážný, aby mu oznámil, že bude vrácen do Saganu. Namísto toho byl ale převezen do Prahy a ironií osudu bylo, že musel eskortu do pankrácké věznice nasměrovat, neboť nikdo z nich předtím v Praze nebyl.

He was interrogated by the Gestapo at the infamous Petschko Palace, where he encountered the Nazi double-agent Augustin Přeučil; a Czechoslovak airman who had also served in the RAF in England before escaping in a Hurricane fighter aircraft to Belgium during a training flight. He now continued to work for his German masters, by identifying captured Czechoslovak RAF airmen who were brought to Petschko Palace for interrogation. Inexplicably Přeučil, who had known Tonder when they were in France together in l’Armee d’Air, claimed that he had not seen Tonder before.

Vyšetřovalo ho gestapo v nechvalně známém Petschkově paláci, kde narazil na německého agenta Augustina Přeučila – československého pilota, německého agenta, který také sloužil v RAF v Anglii předtím, než ve stíhacím letounu Hurricane uletěl během výcvikového letu do Němci okupované Belgie. Teď pokračoval v práci pro své německé chlebodárce tím, že identifikoval zajaté československé RAF letce, kteří se dostali do Petschkova paláce k výslechu. Přeučil, který musel znát Tondera z Francie, když spolu byli v l’Armee d’Air, prohlásil, že Tondera nikdy předtím neviděl.

On 21 November Tonder and Dvořák were transferred from Pankrác prison to Prague’s Hradčanský domeček military prison. On 30 November they were transferred to Stalag Luft I, at Barth. Two weeks later they were taken to Leipzig for a show trial, were they were tried for treason, as by serving in the RAF, they were traitors to the Reich Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren, the new German name for occupied Czechoslovakia. They were sentenced to death and sent to Oflag IVc – Colditz – to await the said execution. *** They were held there until 16 April when the castle was liberated by the Americans.

Dne 21. listopadu byli Tonder a Dvořák převezeni z věznice Pankrác do pražského vojenského vězení Hradčanský domeček. 30. listopadu pak byli přemístěni do Stalag Luft I v Barthu. O dva týdny později byli odvezeni do Leipzigu na soudní přelíčení, kde byli shledáni vinnými ze zrady říšského protektorátu Böhmen und Mähren tím, že sloužili ve službách RAF. Byli odsouzeni k trestu smrti a posláni do Oflagu IVc – Colditz, kde měli čekat na svoji popravu. *** Zde byli drženi až do 16. dubna, kdy byl objekt hradu osvobozen Američany.

_______________________________________________________________

Arnošt Valenta

F/Lt Arnošt Valenta

F/Lt Arnošt Valenta was a 32 year old 311 Sqn wireless operator. On the night of 6/7 February 1941, six 311 Sqn Wellington bombers took off from East Wretham for a bombing raid on Bolougne. Valenta’s aircraft KX-T, L7842 was piloted by F/Lt František Cigoš, with P/O Emil Bušina standing in for Jaroslav Partyk, the crew’s usual navigator. During the return flight, Bušina became ill, disorientated and confused. Valenta’s radio set began to malfunction and they were unable to get navigational assistance by radio. Instead, they had to navigate by dead-reckoning to try and return to base. Instead of flying North to England, they inadvertently flew back to France and mistook the Luftwaffe airfield at Saint-Paul, Normandy, France for an English airfield, and landed. Taxing towards the airfield buildings, they noticed German soldiers running towards them. Realising their mistake, Cigoš hastily tried to take-off, but the Wellington’s wheels had become stuck on the muddy grass airfield and the whole crew were captured.

F/Lt Arnoštu Valentovi bylo 32 let a sloužil jako radiotelegrafista u 311. bombardovací perutě. V noci ze 6. na 7. února 1941 vzlétlo z East Wretham 6 bombardérů Wellington z 311. perutě, aby provedly bombový útok na Bolougne. Valentův letoun KX-T, L7842 byl pilotován F/Lt Františkem Cigošem a nový člen posádky P/O Emil Bušina zaskakoval jako navigátor za nemocného Jaroslava Partyka, obvyklého člena této posádky. Během letu nazpět postihla Bušinu zdravotní indispozice, byl dezorientovaný a zmatený. Valentova radiostanice měla výpadky funkce a nebylo možné získat touto cestou informace o jejich poloze. Aby se dokázali vrátit zpět na základnu v Anglii, museli se pokusit získat informace o své poloze výpočtem. Avšak namísto kurzu na sever k Anglii, nevědomky letěli zpět do Francie a přistáli na letišti Luftwaffe v Saint Paulu v Normandii, které mylně pokládali za letiště v Anglii. Když pohlédli směrem k letištním budovám, všimli si německých vojáků běžících směrem k nim. Uvědomili si svůj omyl a Cigoš se usilovně snažil dostat stroj znovu do vzduchu, ale kola podvozku uvízla v zabahněné trávě letiště a celá posádka byla následně zatčena.

Valenta’s Prisoner of War number was 415, Initially sent to Dulag Luft, at Oberursel, Germany, for interrogation, he was then sent to Stalag Luft 1, Barth on 15 February, then to Stalag Luft III, Sagan, in March ’42. Here, his linguistic skills (he was fluent in French, German, English and Russian as well as his native Czech), coupled with his organisational ability and previous intelligence experience against the Germans, made him a natural choice as the Escape Committee’s Intelligence Officer. He was to become one of the leading protagonists of the Great Escape.

Jeho číslo válečného zajatce bylo 415 a nejdříve byl poslán do Dulag Luft v Oberurselu v Německu na výslech, poté dne 15/02/41 do Stalag Luft 1, Barth a nakonec v březnu 1942 do Stalag Luft III, Sagan. Jeho výjimečné organizační a jazykové schopnosti (mluvil plynně francouzsky, německy, anglicky, rusky, stejně jako česky) spolu s předchozími zpravodajskými zkušenostmi proti Němcům, z něj činily přirozenou autoritu. Díky tomu se uplatnil ve Výboru, který útěk organizoval a stal se jedním z předních protagonistů Velkého útěku.

His Escape:

Jeho útěk

F/Lt Arnošt Valenta’s escape route.

Trasa útěku F/Lt Arnošta Valenty.

His escape partner was F/Lt Henry ‘Johnny’ Marshall, a 3 PRU pilot who was forced to bail out of his Spitfire on 12 January 1941 over Laval, France, and now one of the main tunnel diggers. With Valenta as Müller, an architect, and Marshall as Rougier, a French entrepreneur, they planned to go by train from Sagan to Mitenwalde, about 20 miles South of Berlin, Germany, and from there to Gdansk, on the Baltic coast of Poland, from where they planned to stow away on a Swedish ship which would take them to Sweden. Their back-up plan was to go to Prague, Czechoslovakia. Here they would meet up with Bedřich Dvořák, Des Plunkett, Ivo Tonder and Johnny Stower. From there they would travel South to Yugoslavia, where they would meet up with Tito’s partisans.

Jeho partnerem při útěku byl F/Lt Henry Johnny Marshall, pilot z 3. PRU, který byl 12. ledna 1941 nucen opustit svůj Spitfire nad Laval ve Francii a patřil mezi hlavní kopáče tunelu. Valenta, jako architekt Müller a Marshall jako francouzský podnikatel Rougier, plánovali odjet vlakem ze Saganu do Mittenwalde, asi 30 kilometrů jižně od Berlína a odtud do Gdaňska na pobřeží Baltského moře v Polsku. Zde se chtěli dostat na nějakou švédskou loď, která by je dopravila do Švédska. Záložní plán byl přes Prahu, kde by se setkali s Bedřichem Dvořákem, Des Plunkettem, Ivo Tonderem a Johnnym Stowerem. Odtud by pak odjeli na jih do Jugoslávie a přidali by se k Titovým partyzánům.